We are conducting a survey to get community feedback about renaming the 1968 Riot Collection.

Please participate in the survey.

The story of the 1968 Uprising is a story about Kansas City in 1968 just as much as it is a story about Kansas City in 2020. Most discussions of the Uprising start with the events of April the 9th with the walk-out and marches. This did not begin on April the 9th, or April the 8th, or even April the 4th as the title of this exhibit suggests. What we hope to communicate on these panels is the story of the Uprising, and the culture and environment of oppression that led to it.

Click on images for more information and links to access related digital content and other online content. Use the arrows to move from page to page.

All photographs and oral history transcripts, unless otherwise noted, are from MS 235 1968 Riot Collection, LaBudde Special Collections, University of Missouri-Kansas City.

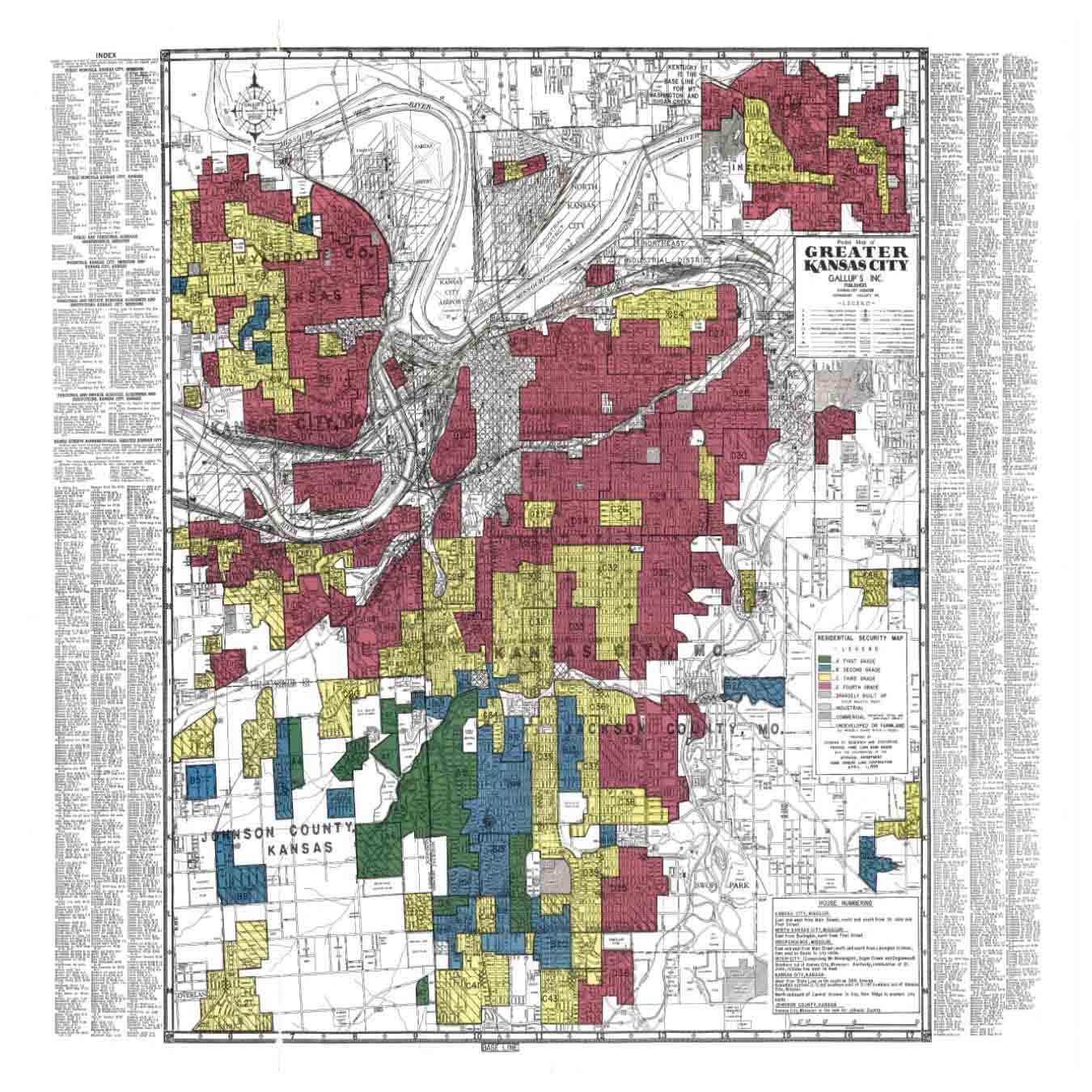

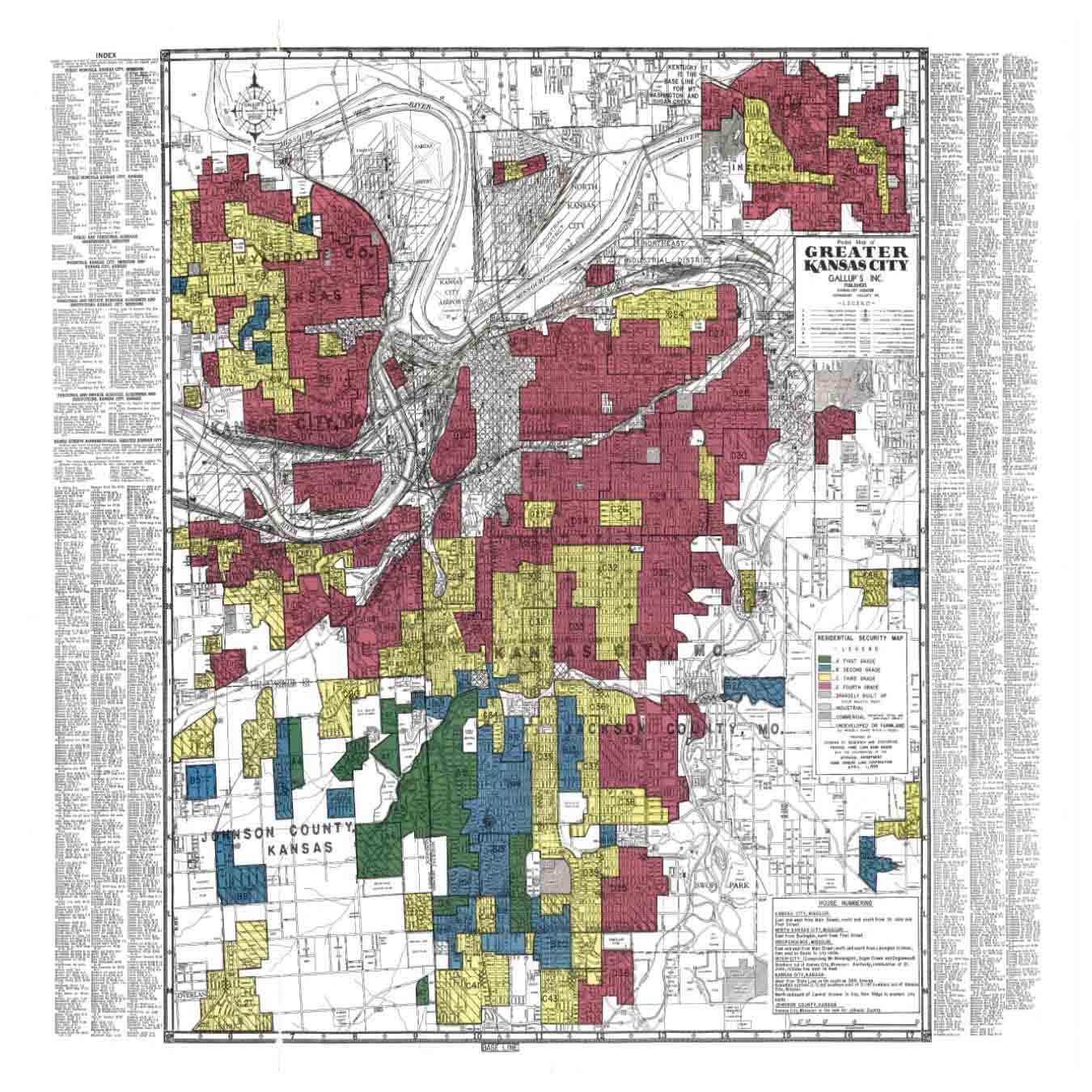

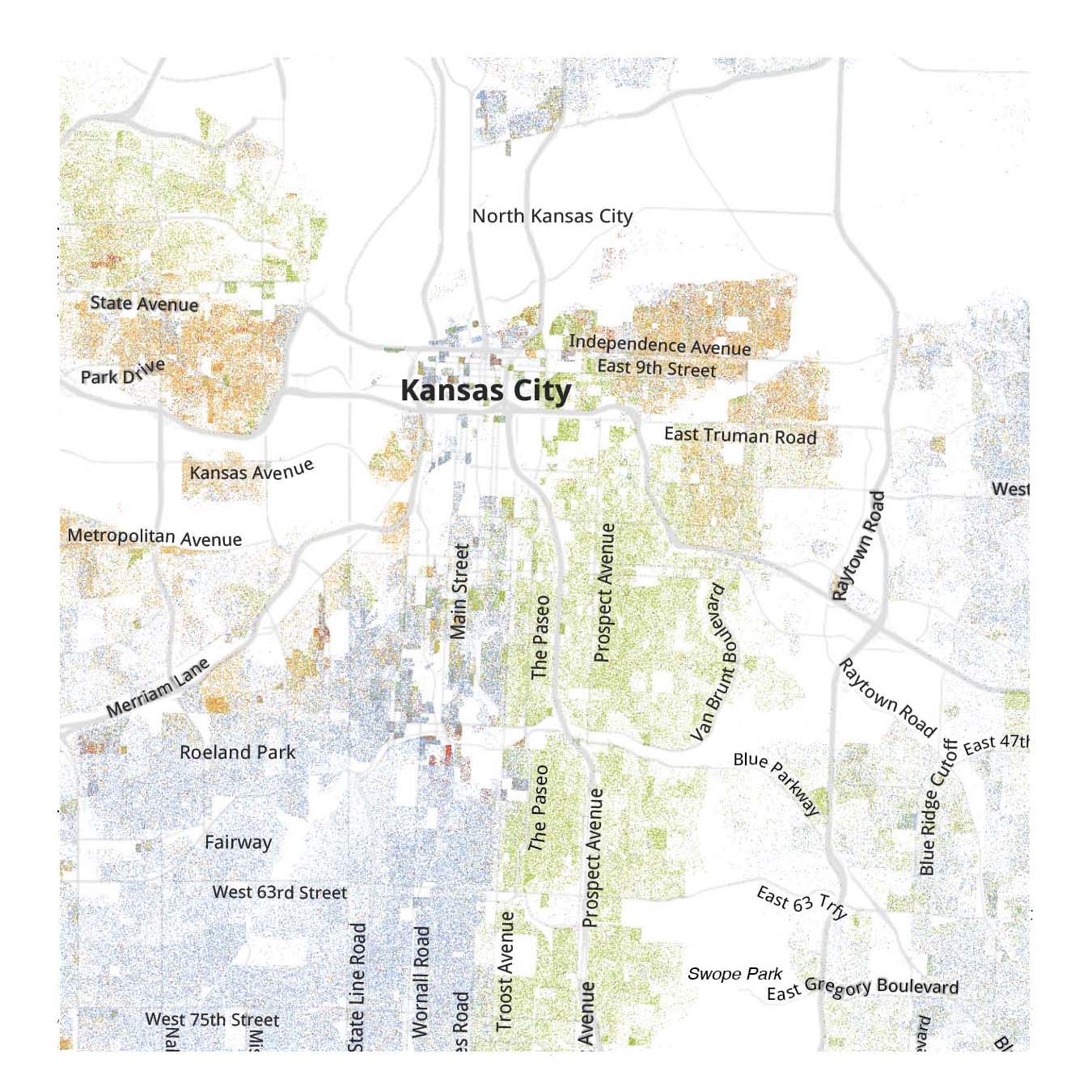

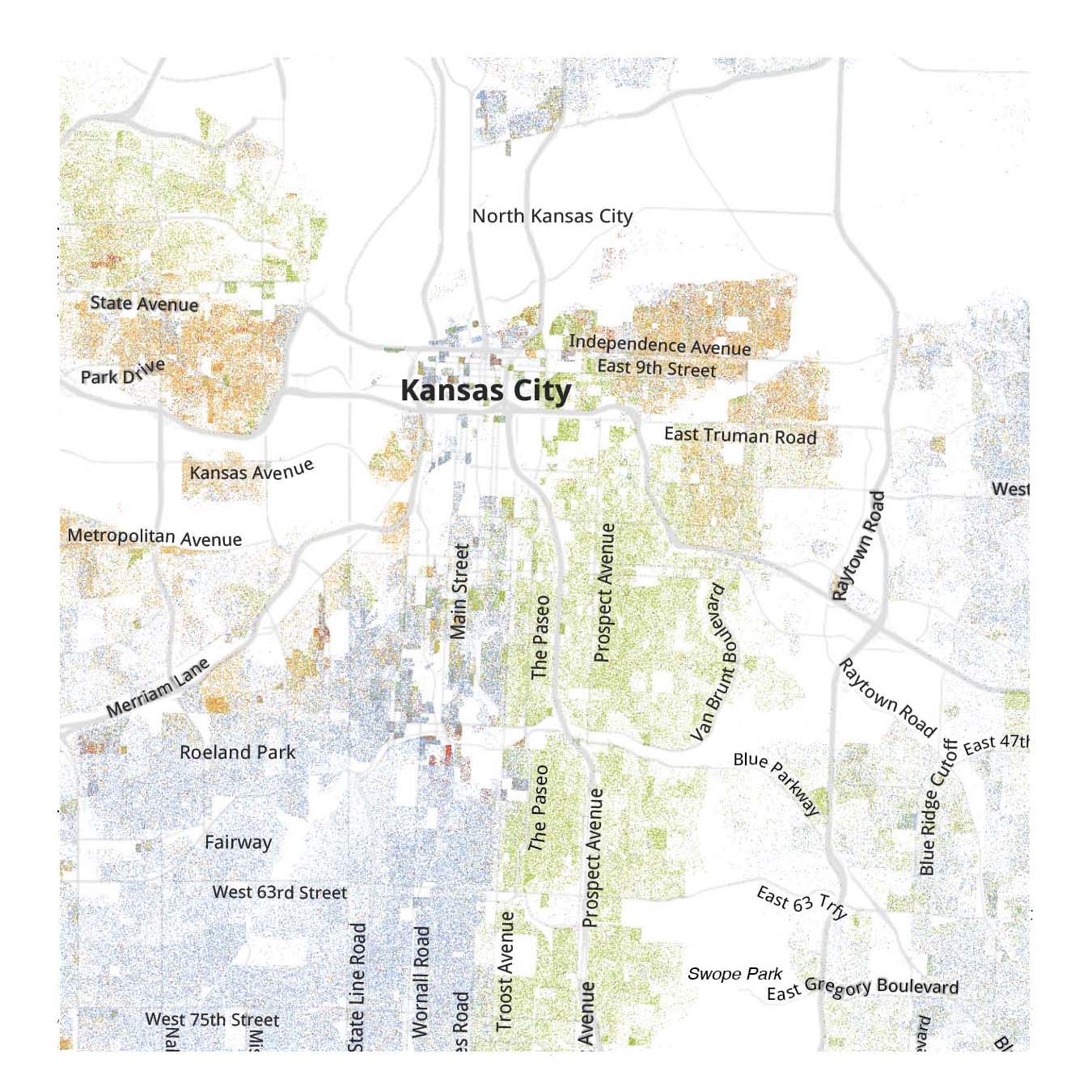

Redlining

Redlining is one of the most important factors that contributed to the climate of social unrest in Kansas City leading up to the events of 1968.

It is a discriminatory practice by which banks, real estate, and insurance companies limit or refuse loans within specific geographic areas, especially those that are predominantly Black. Redlining first came about as an evaluation policy developed by the Home Owners' Loan Corporation (HOLC) following the Great Depression.

These maps show the impact this disastrous economic practice has had over time by severely segregating Kansas City and creating both physical and economic borders between neighborhoods. The devaluation of these homes has created a wealth gap where the median wealth of white families is currently 12 times higher than that of Black families.

Public Accommodations

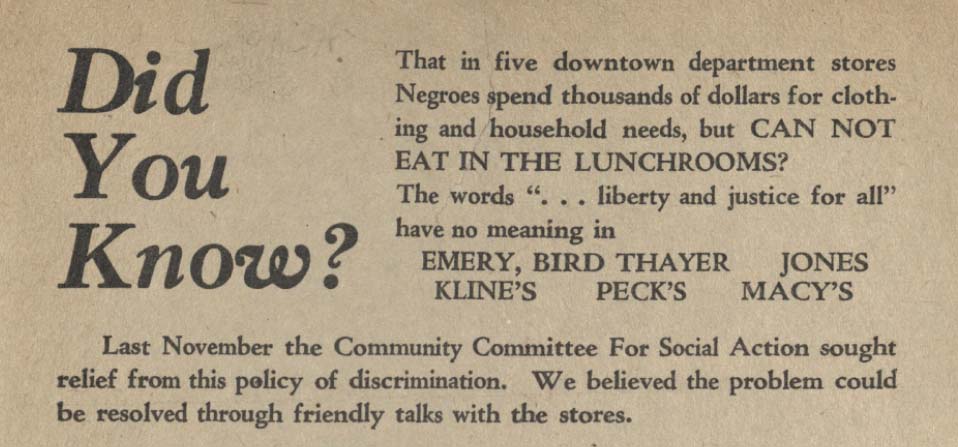

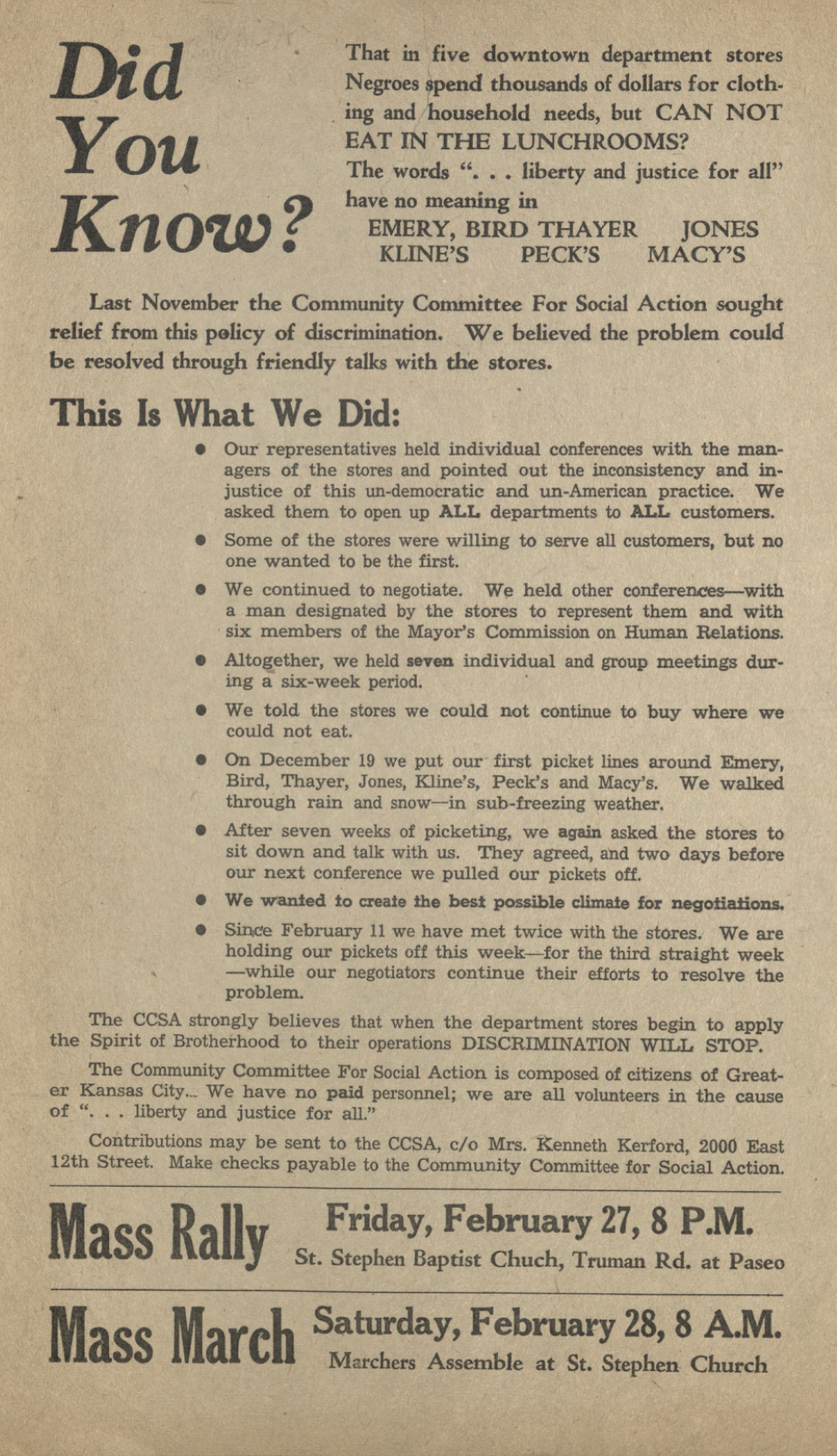

Department Store Protests

In the winter of 1958, the Community Committee for Social Action (CCSA), led by activist and elementary school teacher Gladys Twine, protested against several downtown department stores for segregating their cafeteria areas. Members organized to cancel their accounts, write letters, and picket the stores until eventually, an agreement was reached between the CCSA and department store owners to desegregate their stores.

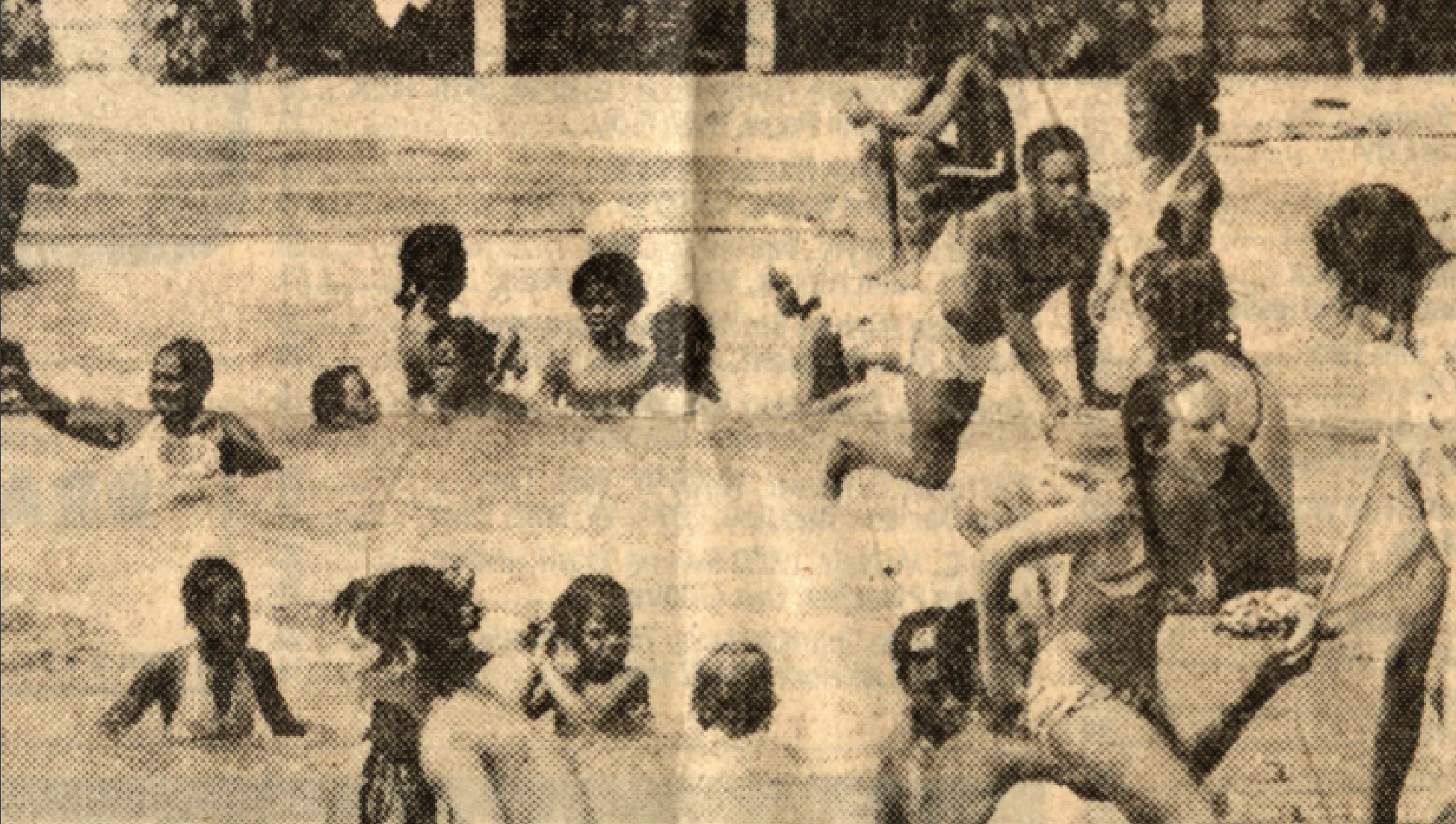

Swope Park Pool Desegregation

In April of 1952, the NAACP, represented by attorney Thurgood Marshall, sued the City of Kansas City, Missouri to desegregate the Swope Park Pool. The judge ruled in favor of the plaintiffs and denied an appeal made by the City shortly thereafter.

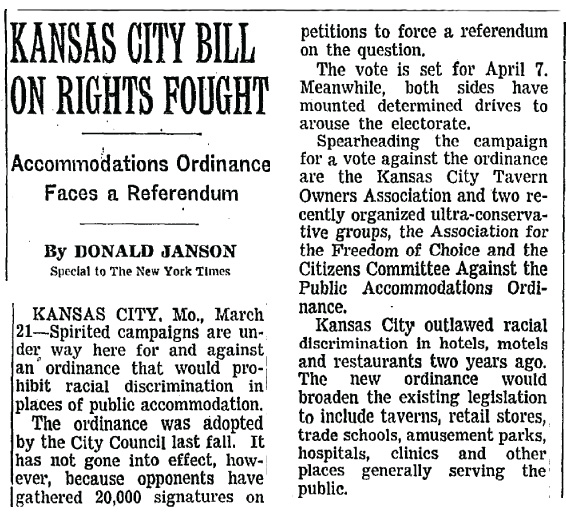

Public Accommodations Ordinance

In the fall of 1963 the City Council adopted a Public Accommodations Ordinance that would ban segregation in the city. The Council received intense backlash, and after opponents had gathered over 20,000 signatures, a referendum was forced on the question. The issue would persist on a case-by-case basis until the events of April 1968.

MICA

Throughout the Uprising, the Metropolitan Inter-Church Agency (MICA) had been utilizing a network of volunteers and activists they had developed months before. In February of 1968, MICA formed their Communication Center as a support system for the Black community of Kansas City, in addition to small teams of clergy, social workers, and lawyers that were to be dispersed throughout the city. The purpose of these teams would be to travel to police outposts to ensure those who were arrested had support and safe travel. There were also individuals who would relay information back to the organization to corroborate or refute reporting from the police outposts and local media.

In his 1973 thesis “Social Organization, Social Tension, Social Change: The Role of Intermediary Groups,†Alvin L. Brooks describes why groups like MICA’s Communication Center form, and how distrust of city and state institutions spreads in such a climate, "When the institutions of the society no longer coincide with the values and aspirations of particular groupings in the society, then those institutions will become illegitimate and those groupings become alienated." The numerous ways in which Jim Crow segregation was propagated over time contributed to a climate in which civil disturbance was likely, if not inevitable in Kansas City.

From Grief to Resolve

The FBI’s surveillance program, COINTELPRO, actively sought to discredit, disrupt, and threaten Dr. King during his lifetime, and a later investigation found that they, “failed to investigate adequately the possibility of conspiracy in the assassination.â€1 These practices, fueled by FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover’s personal dislike of King, support the conclusion that the FBI was complicit in the assassination.

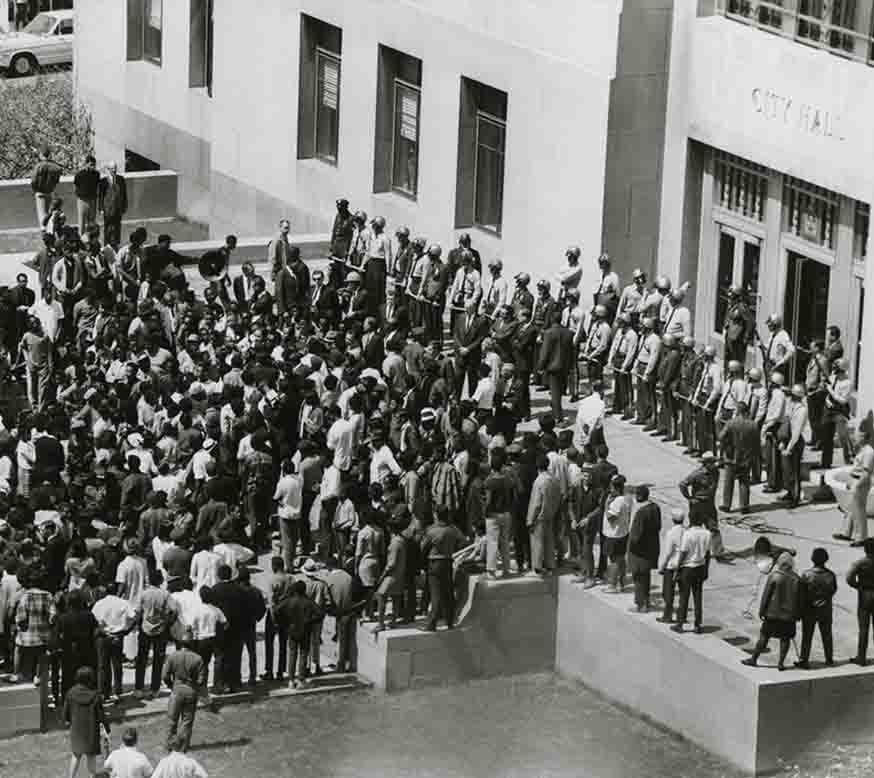

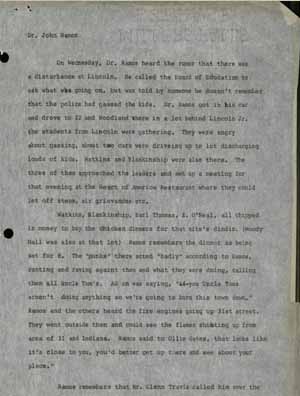

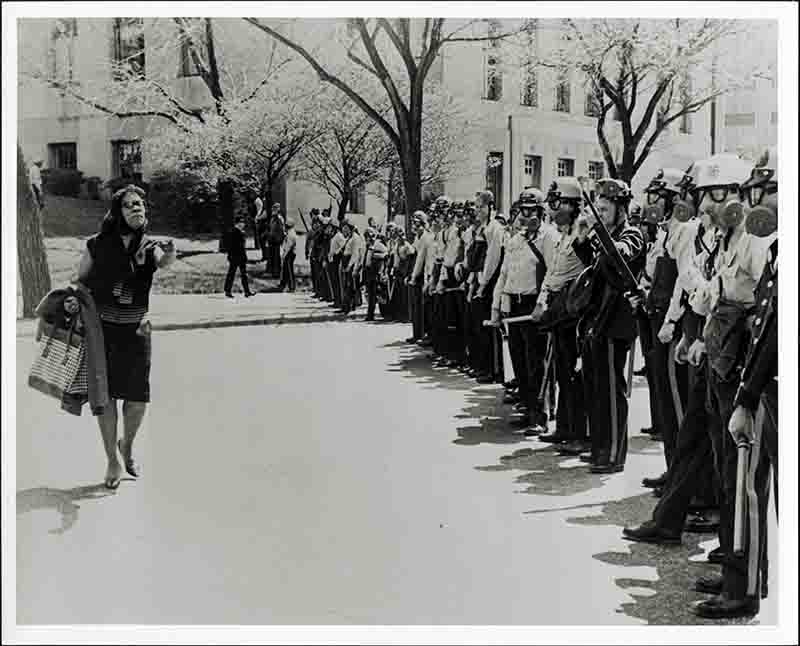

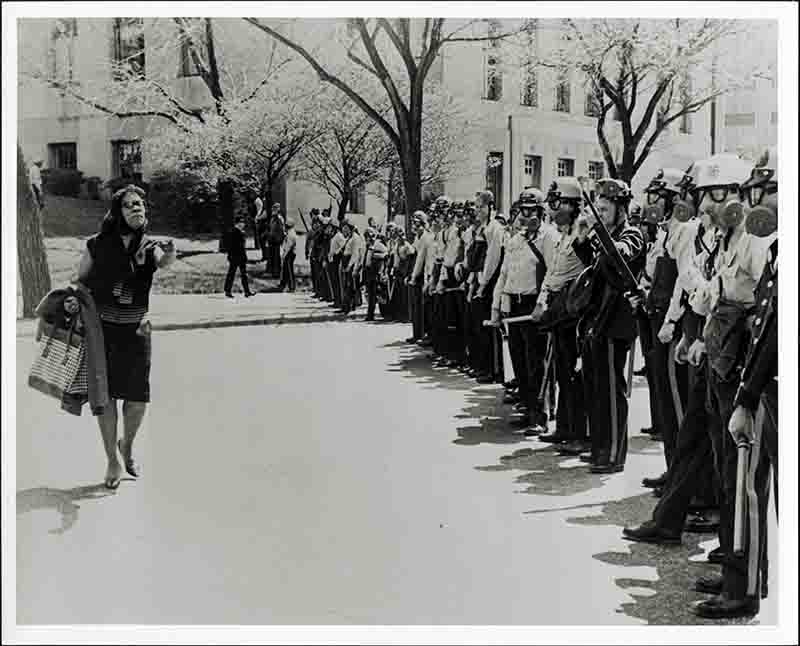

To the Steps of City Hall

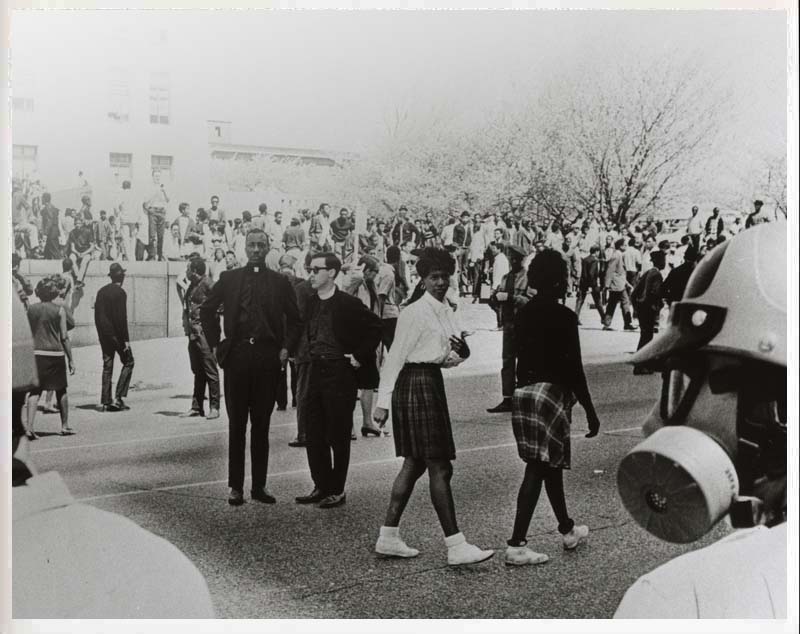

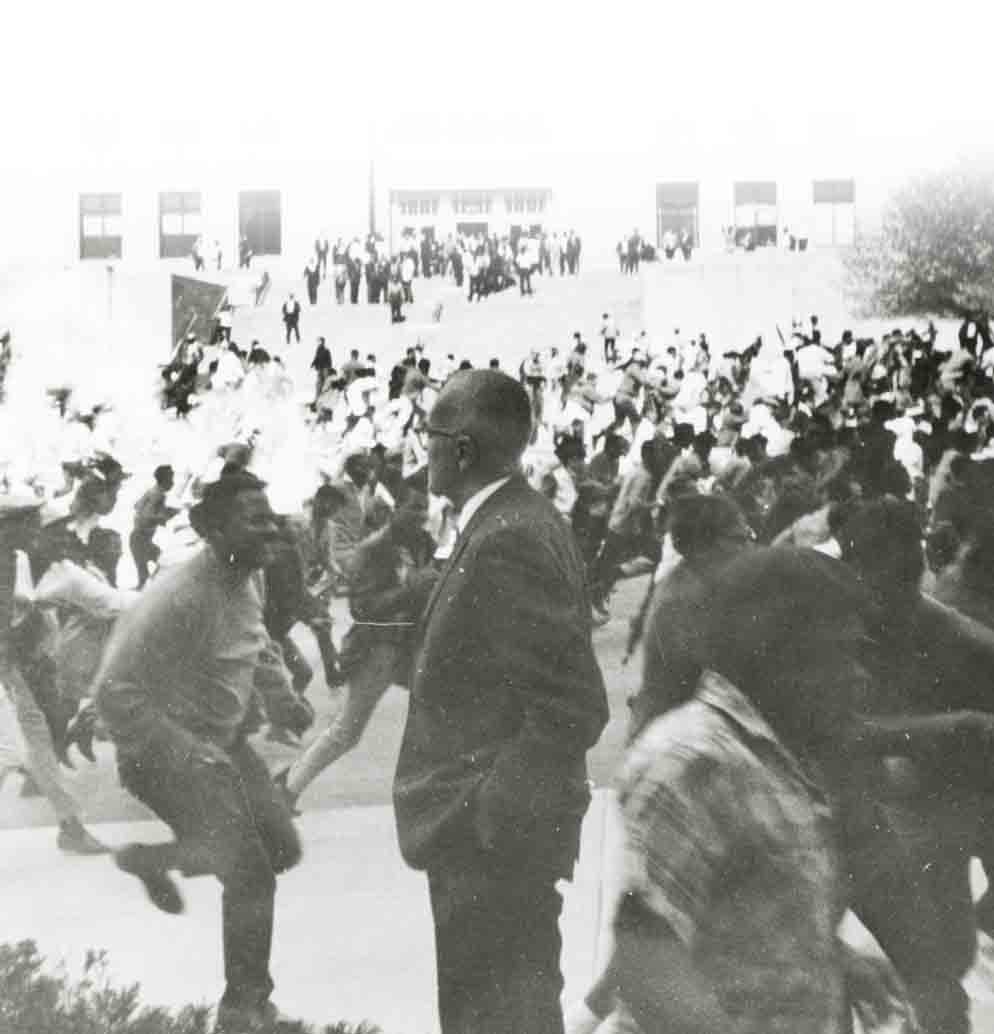

In the days leading up to the walk-out, police had been developing a plan of action should any civil disturbance take place. They mobilized quickly, posting officers outside of the schools to keep an eye on students, even having a helicopter survey from above. The police were present for every step of the march, armed with tear gas, billy clubs, rifles, pepper spray, and dogs. Civil leaders such as Bruce R. Watkins, Herman A. Johnson, Alvin Brooks, Curtis McClinton, and Lee Bohannon joined the students early on in order to ensure they were both organized and safe.

Marchers gathered at Parade Park as they marched forward. Originally intending to go to the School Board, the group stopped at the park to regroup. Among the speakers at this gathering were Mayor Ilus Davis, who spoke through a bullhorn on top of a car. At one point, the marchers split into two groups, one heading directly towards City Hall, and one traveling down I-70 in the opposite lane of traffic.

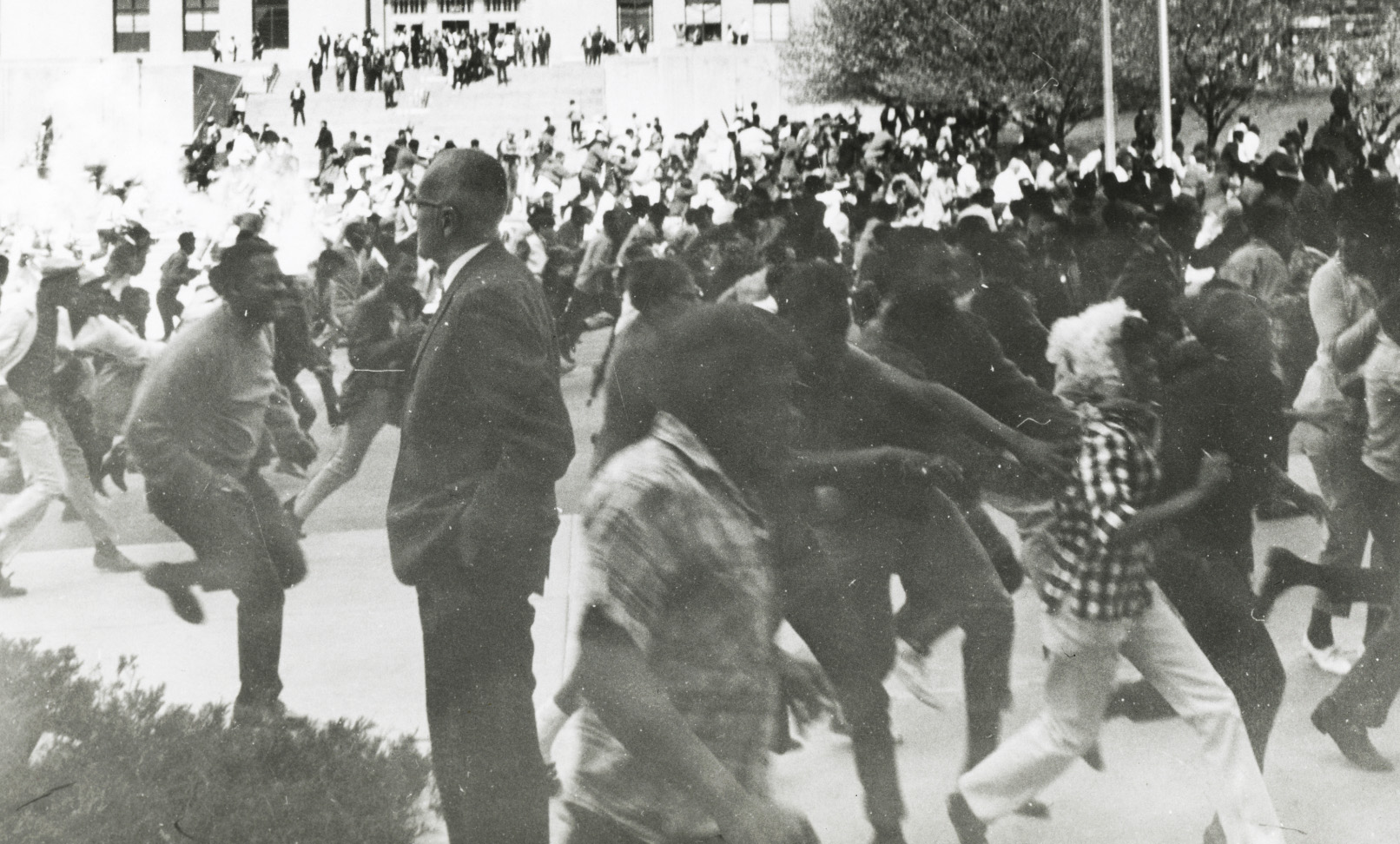

Chaos Erupts

Once students were at City Hall listening to their leaders speak from the steps, John L. Frazier, a local DJ, had the idea to gather buses for the students to ride out on safely. The buses would transport students to Holy Name Church where they could relax and unwind.

Before students could move to the buses, someone threw a pop bottle over the police line, hitting an officer in the foot. The police chose to respond to this by throwing tear gas into the crowd, charging, beating, and arresting marchers and students. The call to implement Tactical Alert Phase II, or a total mobilization of police force, was made at 8:50am, five minutes after Sgt. Robert Arndt says the first canister of tear gas was thrown.

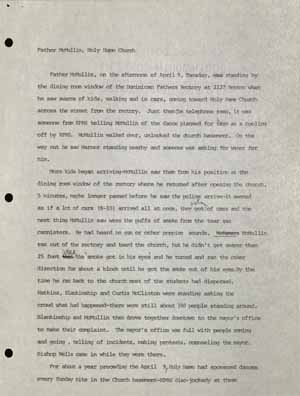

Holy Name

Students that were able to make it to Holy Name Church were recovering from the events at City Hall when a small group of students came bursting into the basement. They had been followed by police officers who promptly exited their vehicle and threw tear gas directly into the church basement. Upon news of this, Herman Johnson, Chapter President of the Kansas City NAACP led other civic leaders in demanding a public apology from the Mayor and Police Chief Clarence Kelley. While the Mayor would later give the apology, Chief Kelley, who vehemently opposed it, did not. That evening, Mayor Ilus Davis issued a proclamation establishing both a state of emergency and a curfew from 9:00 pm to 6:00 am.

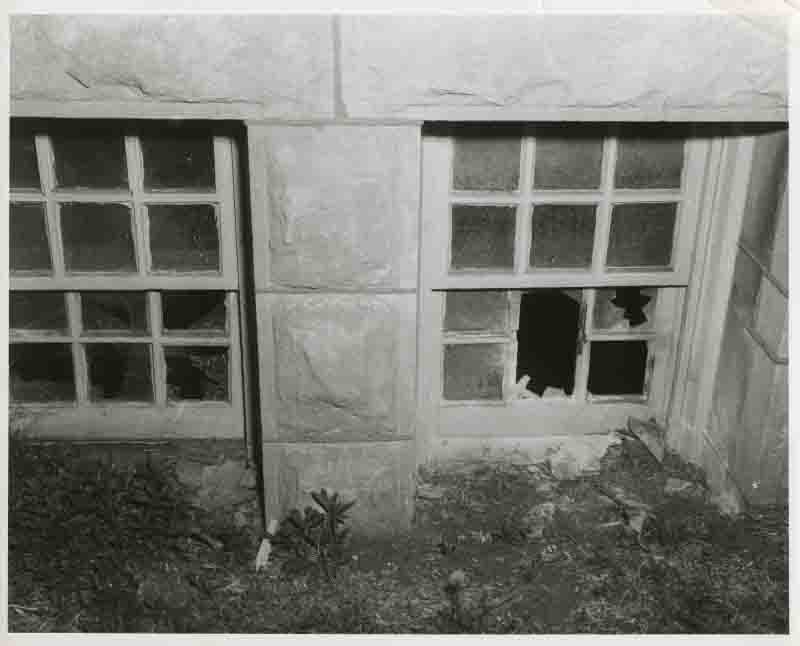

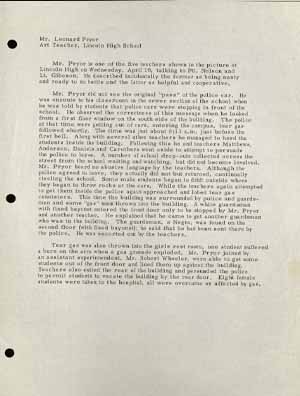

Lincoln Highschool

[Leonard Pryor] was enroute to his classroom in the newer section of the school when he was told by students that police cars were stopping in front of the school ... The police at that time were getting out of cars, entering the campus, tear gas followed shortly. The time was just about 8:13 a.m. just before the first bell … Although the police agreed to leave, they did not but returned, continually circling the school ... While teachers again attempted to get them inside the police again approached and lobed [sic.] tear gas canisters … Tear gas was also thrown into the girl’s restroom, one student suffered a burn on the arm when a gas grenade exploded … Eight female students were taken to the hospital, all were overcome or affected by gas.â€

- Leonard Pryor interview, 1968 Riot Collection, LaBudde Special Collections

The Byron Hotel

APRIL 10: In the evening, patrols were called to an area of “high activity†around the 30th and Prospect intersection on Kansas City’s East Side. One national guardsman, William Jewett, was struck in the arm by a bullet. Though Jewett wasn’t sure if what he had seen was “a cigarette lighter or a gun,†he identified the shot as coming from the Byron Hotel across the street, after which police and guardsmen proceeded to pepper the building and surrounding area with return fire. Police and guardsmen shot out all streetlights in the surrounding block, blanketing the streets in darkness. When all was said and done, four people were dead.

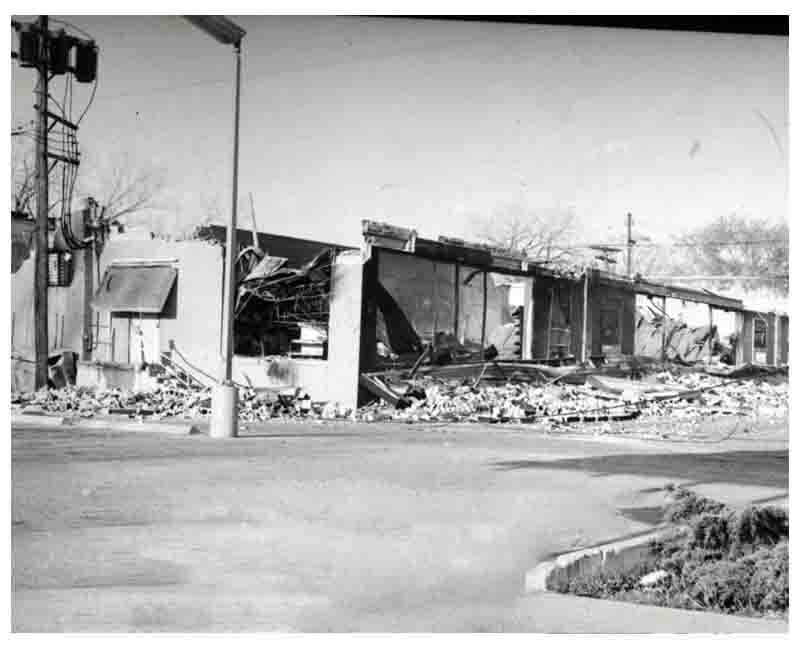

APRIL 11: By this time, most of the activity had dwindled. The City Council passed an ordinance that allowed for fines and jail time to any curfew-breaker caught out. Aside from several unsubstantiated reports of violence, activity slowed throughout the day. At the conclusion of the chaos, damages reached an estimated $4 million, or roughly $29 million today. Hundreds were arrested, dozens injured, and six people were killed. The area of highest activity, around 31st and Prospect, was virtually razed to the ground by fires.

In Memory

Riots sparked in almost every major city in the United States in the wake of Dr. King's death, from Chicago to Washington DC to Baltimore and beyond. In the course of these events, dozens of citizens were killed. In Kansas City, six civilians were shot by police. These are lives that were not lost, but taken. This injustice reverberates loudly today as we continue to lose Black lives to the violence of the police and the institutional indifference of those meant to hold them accountable. Words cannot express the senselessness of all of these deaths, spanning generations. So for those taken in 1968, we honor their lives. Rest in power.

Maynard Odell Gough was born in Kansas City, MO and worked as a surgical technician at Kansas City General Hospital, where he was often also a patient due to sickle cell anemia.

Julius Preston Hamilton was a son, husband, father to two, and brother to six. He was born in Kansas City, where he lived his entire life. He worked as a bricklayer and enjoyed bowling, fishing, and hunting.

Hamilton was fatally shot by police through a screen door while standing in his own house, unarmed, on April 10th, 1968. According to a report by the Board of Police Commissioners, the officer who murdered Hamilton “insisted he thought the victim was armed and standing outside on a porch and in a position to endanger a fellow officer emerging on 30th Street between apartment buildings.†He is buried in Lincoln Cemetery.

Two months after Julius Hamilton's death, his wife, Leona Hamilton, requested a public hearing and investigation into the circumstances surrounding the shooting. The evidence gathered directly contradicted the initial report of the officer who shot Hamilton, yet due to sovereign immunity, his family was not able to seek justice from the police department. Mrs. Hamilton's lawyers sent the Police Board of Commissioners, along with numerous political figures, a summary of the proceedings with a Call to Action to address issues of accountability. Read the full report (PDF).

Known to many as “Shugg,†Charles Martin, Jr. was a husband, father to two, son, and brother to ten. He served in the U.S. Army, was a welder by profession, and spent most of his life in the Kansas City area.

Martin was fatally shot by police on April 10th, 1968 while fleeing gunfire at the Byron Hotel. A report says that Martin was drinking and eating candy in the parking lot next to the Byron Hotel when a police officer approached him and asked him to move. Martin dropped his candy wrapper and stooped to pick it up. When he stood up again he was shot. He is buried in Woodlawn Cemetery.

Albert Daniel Miller, Jr. was a father of one, son, grandson, great grandson, nephew, brother to two, and half-brother to six. He spent his whole life in Kansas City, where he was a city employee and a member of Zion Grove Baptist Church.

Miller was fatally shot by police on April 10th, 1968 attempting to cross a barricade while fleeing gunfire at the Byron Hotel. He is buried in Lincoln Cemetery.

George McKinney, Sr. was born in Elwood, KS, just across the river from St. Joseph, MO and moved to Kansas City in 1943. He was a husband, father to ten, including George McKinney, Jr., brother to five, and grandfather to four. He was a window washer and Baptist minister.

George McKinney, Jr. was a son, grandson, nephew, and brother to nine. He was a lifelong resident of Kansas City and student at Central Junior High School, where he was a member of the wrestling, football, basketball, and baseball teams.

Both McKinneys were fatally shot by police on April 10th, 1968 while exiting a grocery store across the street from the Byron Hotel, a block away from their home. They are buried in Highland Cemetery.

Conclusion

The Public Accommodations Referendum was set to be voted on on April 30th of 1968. On April 11th, the United States Congress passed the 1968 Civil Rights Act. At the same time, the City Council of Kansas City unanimously passed the housing provisions of the CRA, effectively nullifying the local referendum and passing the Public Accommodations Ordinance into law. It is held by some that had the uprising not occurred, the ordinance never would have passed.

The story of Kansas City in 1968 is the story of Kansas City in 2020. It is not "Then and Now", it was and still is "Now". We, as a community, still feel the impact of redlining and institutional isolation. The Prospect Corridor has not yet been restored to what it was before 1968. Often enough when discussing these events, the impetus seems to be to placate the guilt of complicity by saying "Look how far we have come". When we began work on this exhibit in the fall of 2019, we sought to bring contemporary significance to a historical event, and following the murders of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, Donnie Sanders, and countless others, and the rebellions that erupted across the world after, we recognize we never needed to. The question is not "How far have we come?" because that question negates the structural, institutional, and physical harm that continues to fester in our society. At this point, there are no more questions to be asked; we already know the answers. At this point, there are only demands to be made, and changes to be enacted.

Exhibit Background

In the fall of 2019, the Prospect Business Association reached out to the University of Missouri-Kansas City’s LaBudde Special Collections about presenting an exhibit about the 1968 Uprising in Kansas City, MO at the Bruce R. Watkins Cultural Heritage Center. This was not the first time UMKC Libraries had presented an exhibit on the topic, nor was it the first time the Prospect Business Association had reached out regarding such an exhibit. In 2018, the PBA approached UMKC Libraries about the previous exhibit and its bias against the Black community. Around the same time, UMKC Libraries employees Anthony LaBat and Sandy Rodriguez began their own investigation and formal critique of the exhibit, which led to a presentation at the Missouri Library Association called The Thin White Line that explored ethical descriptions, implicit bias, and how language contributes to oppression using the 2018 exhibit critique as a case study.

This exhibit tackles the same subject matter as the original 2018 exhibit but with a reframing of the subject matter based on LaBat and Rodriguez's study. Some of the most impactful changes occurred behind the scenes, with a more robust system for collaboration, communication, and review. In addition, LaBudde Special Collections is currently conducting a survey to get input on the potential renaming of the ‘1968 Riot Collection’ and the collection finding aid has been updated to account for and remove harmful biased language.

We are conducting a survey to get community feedback about renaming the 1968 Riot Collection.

Please participate in the survey.

Acknowledgements

Bruce R. Watkins

Cultural Heritage Center

Glenn North

Executive DirectorBruce R. Watkins Cultural Heritage Center

Elbert Anderson

Co-Founder,Prospect Business

Association

Dr. Anthony LaBat

LaBudde Special Collections,University of Missouri-Kansas City

Lindy Smith

Head of LaBudde Special Collections,University of Missouri-Kansas City

Dee Evans

Associate Director of External Relations,University of Missouri-Kansas City

Prospect Business

Association

Sandy Rodriguez

Associate Dean of Special Collections& Archives,

University of Missouri-Kansas City

Dr. Delia Gillis

Professor of History & Africana Studies,University of Central Missouri

Additional Resources

Explore More

-

Eight Days in April: Race, Rebellion, and Reconciliation Exhibit opening panel discussion, February 18, 2021

-

1968 Riot Collection LaBudde Special Collections, University of Missouri-Kansas City

-

1968 Riot Collection Photographs Digital Special Collections, University of Missouri-Kansas City

-

The Thin White Line Anthony LaBat. Presented at the Educate-Organize-Advocate Conference, University of Missouri-Kansas City, October 30, 2019

-

‘68: The Kansas City Race Riots Then and NowKansas City Public Television. Filmed March 2018 at the Plaza Library, Kansas City, MO

-

Prospect Avenue Nodal Study KCDC, Kansas City Design Center

Audio Clips and Transcripts

Arrests Mean Nothing Without Conviction, Lena Rivers Smith

MS 210 Walt Bodine Collection, Recording 0407-0101, Marr Sound Archives, University of Missouri-Kansas CityThe Divisiveness of The Looting and Economic Disparity (MP3)

MS 210 Walt Bodine Collection, Recording 0231, Marr Sound Archives, University of Missouri-Kansas CityInterview - Members of the Black Community on Demands and What the Police Can Do

Is It a Riot or Civil Disorder? Who Decides?: Walt Bodine, Lena Rivers Smith, and Tom Leathers

MS 235 1968 Riot Collection, Recording 002-0201, LaBudde Special Collections, University of Missouri-Kansas CityNews Bulletin: 'Youths Booked', National Guard Called

MS 235 1968 Riot Collection, Recording 002-0101, LaBudde Special Collections, University of Missouri-Kansas CityNight Beat: Walt Bodine Interviews Mayor Ilus Davis

MS 235 1968 Riot Collection, Recording 003-0101, LaBudde Special Collections, University of Missouri-Kansas CityPolice Dispatch: Volunteers for Ambulances

MS 235 1968 Riot Collection, Recording 003-0101, LaBudde Special Collections, University of Missouri-Kansas CityPolice Dispatch: Weiners Store

MS 235 1968 Riot Collection, Recording 003-0101, LaBudde Special Collections, University of Missouri-Kansas CityStatement: This is Frustration

MS 235 1968 Riot Collection, Recording 002-0201, LaBudde Special Collections, University of Missouri-Kansas CityStatement: Police & Power, 1968 Riot Collection

MS 235 1968 Riot Collection, Recording 002-0201, LaBudde Special Collections, University of Missouri-Kansas CityWHB News Time Bulletin: Downtown Fires

MS 235 1968 Riot Collection, Recording 002-0101, LaBudde Special Collections, University of Missouri-Kansas CityWhite Journalists Don't Know Anything

MS 210 Walt Bodine Collection, Recording 0407-0101, Marr Sound Archives, University of Missouri-Kansas City