A CLAP OF THUNDER HERALDED THE PASSING OF CHARLIE "BIRD" PARKER. Baroness Pannonica de Koenigswarter, who gave Parker refuge and comfort during his final days in her suite in the Hotel Stanhope on 5th Avenue in New York, recalled, "At the moment of his going, there was a tremendous clap of thunder. I didn't think about it at the time, but I've thought about it often since; how strange it was." One musician speculated that Parker disintegrated into "pure sound."

Charlie Parker had lived life to its fullest. Robert Reisner, a friend of Parker and author of Bird: The Legend of Charlie Parker, observed, "Charlie Parker, in the brief span of his life, crowded more living into it than any other human being. He was a man of tremendous physical appetites. No one had such a love of life, and no one tried harder to kill himself...." Dr. Richard Freymann, the attendant physician during Parker's final days at the Stanhope Hotel, judged him fifty-three years old. He was thirty-four at the time of his death.

Parker's early death came as no surprise to those who knew him well. After becoming hooked on heroin at the age of sixteen, he struggled with drug addiction, alcohol abuse and mental illness for the rest of his life. Over the years, his massive consumption of alcohol and drugs ravaged his already fragile physical and mental health.

Nevertheless, during his short life, Parker changed the course of music. Like Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Miles Davis and John Coltrane, he was a pioneering composer and improviser who pioneered a new era of jazz and influenced subsequent generations of musicians.

Parker's brilliance and charisma also inspired dancers, poets, writers, filmmakers and visual artists. Jack Kerouac emulated Parker's improvisational style in his poem "Mexico City Blues". Clint Eastwood paid homage to Parker's tortured genius with his film Bird. In 1984, the Alvin Ailey Dance Company celebrated Parker with For "Bird" With Love. Artist Jean-Michel Basquiat honored Parker with many artworks including Charles the First. In 2015, an opera based on his life Charlie Parker's YARDBIRD made its debut at the Kimmel Center in Philadelphia. Parker's vast influence continues today with hip-hop artists and other kindred musical spirits sampling his music, confirming that BIRD LIVES!

Early Bird

BORN IN KANSAS CITY, KANSAS, Charlie Parker came of age musically while hanging arond the alleyways behind the nightclubs that lined 12th Street in Kansas City, Missouri. On August 29, 1920, Doctor J. R. Thompson delivered Charlie in the family's two-room apartment at 852 Freeman Avenue. Like many other African Americans, Charlie's parents, Addie and Charles Senior migrated to Kansas City from the south, Addie hailed from Southeastern Oklahoma. Charles, the son of a minister, traveled widely across the south.

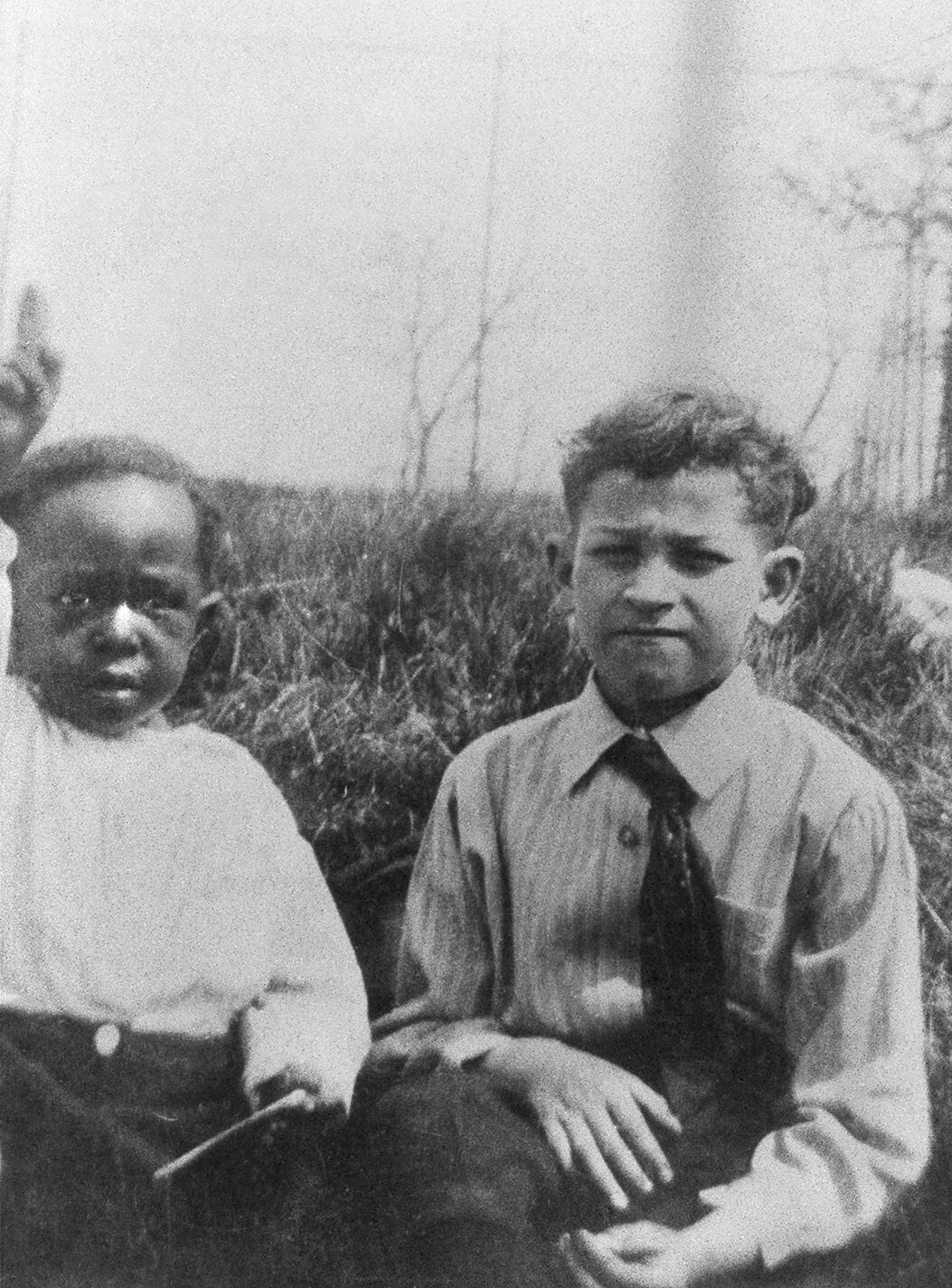

Charles, Sr. worked as a Pullman Porter on the Railroad. Addie, a doting mother, spoiled Charlie, a pudgy precocious child with a cherubic smile. She dressed him in the finest clothes and fussed over his long hair. Charlie walked at eleven months and began speaking complete sentences at two years old. Charlie adored his half- brother John Anthony Parker, who lived up the hill with their grandmother.

In 1927, Charlie's family moved to a spacious apartment at 3527 Wyandotte, located in the heart of a middle class neighborhood in Kansas City, Missouri. Charles. Sr. worked as a janitor in an apartment building on the corner of 36th and Wyandotte. When the owners of the apartment building converted it to condominiums in 1930, the Parker family moved around the corner to 109 W. 34th St. Both buildings stand today.

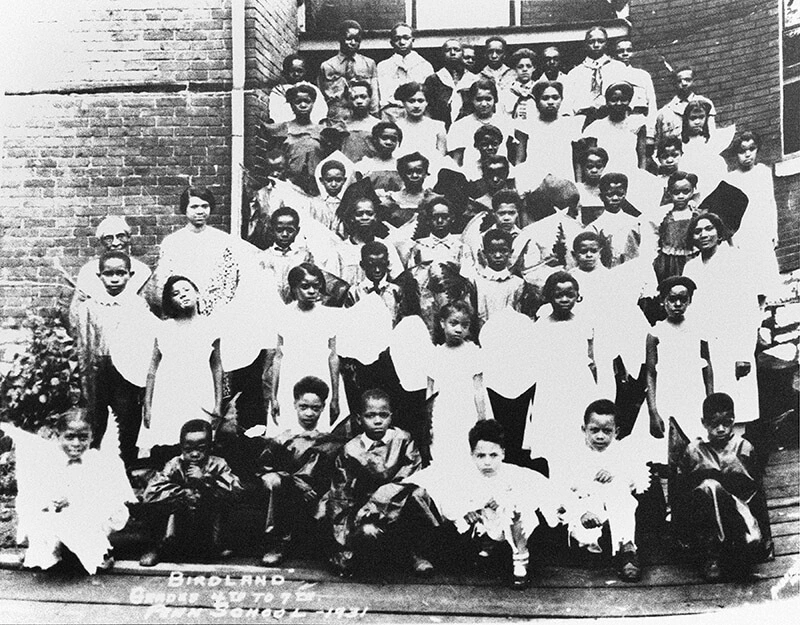

Charlie attended Penn School, in Westport, located in a mixed race community a mile south of the family's apartment. Named after William Penn, Penn School was the first school established west of the Mississippi River to educate African American students.

Bird & Ikey

1535 Olive St

1516 Olive St

Penn School

109 W. 34th St.

3527 Wyandotte

First in Flight

IN 1932, ADDIE AND CHARLES SR. SEPARATED. Charles, Sr. drifted off and Addie rented a two-story brick house at 1516 Olive Street, located northeast of 18th and Vine, the heart and sould of the African American Community. Addie found work as a custodian for Western Union in Union Station, Kansas City's grand railway station. Charlie finished grade school at Sumner School at 2121 Charlotte Street.

In 1933, Charlie enrolled in Lincoln High School, Kansas City's only high school for African Americans. Charlie gravitated to Lincoln's acclaimed music program. Charlie, having loaned his alto to a friend picked up the baritone horn. Addie did not like the look of the baritone, so she bought him another alto saxophone. Charlie played in the band and orchestra.

In the summer of 1935, Charlie joined the Twelve Chords of Rhythm, a young band led by Lawrence Keyes. The Chords played dances, social engagements and Sunday nights at Lincoln Hall, a popular dance hall located on the corner of 18th and Vine.

After hours, Charlie continued his musical studies in the alleyways behind the nightclubs lining 12th Street. Addie worked nights and after she left for the evening, Charlie made his rounds of clubs with his friend Ernest Daniels. His favorite roost was the balcony above bandstand at the Reno Club where the Count Basie Band held court. Basie hosted a jam session that started Sunday night and continued all day Monday. Jam sessions in Kansas City became a rite of passage for young musicians.

The Reno Club

The Mutual Musicians Foundation Photograph Collection, LaBudde Special Collections, UMKCRising stars

Article in The Kansas City Call noting the rising popluarity of Lawrene Keyes new band.

Saxophonist Supreme

On Thanksgiving Day, 1936, Charlie traveled with a band to play the grand opening of Musser's Ozark Tavern, located near Eldon, Missouri. On the way, the car Charlie was traveling in hit a slick spot and flipped over. The force of the accident killed the bandleader George Wilkerson and fractured Charlies' back and ribs. Charlie convalesced at home under the watchful eye of Addie.

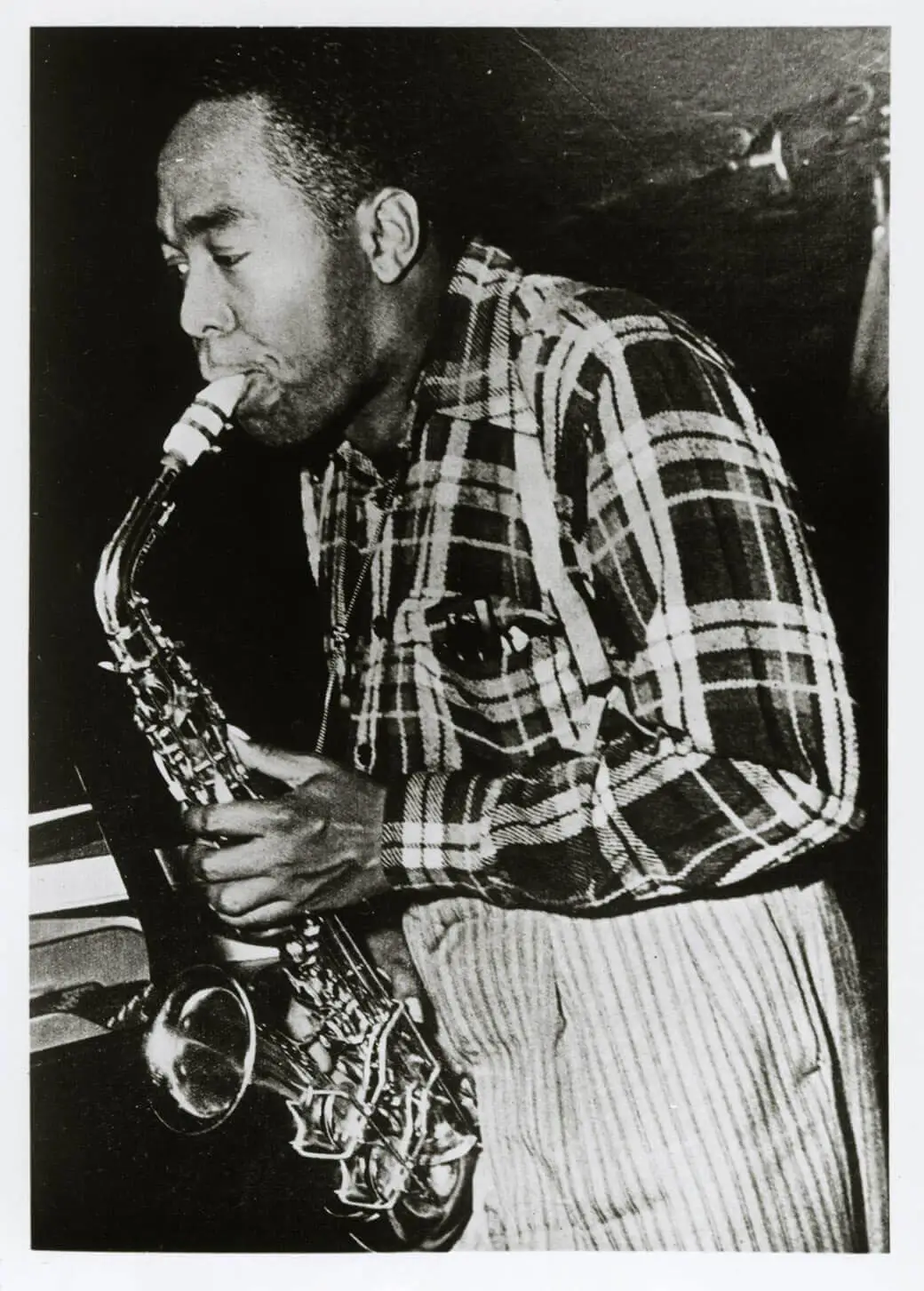

In the summer of 1937, Charlie played and extended engagement with the George E. Lee Band at the Ozark Tavern. Surrounded by racially hostile territory, band members kept a low profile and stayed at the resort. After hours, Charlie practiced his saxophone, mastering chord changes, substitutions, voicing and inversions. Charlie came of age musically that summer spent in the Ozarks.

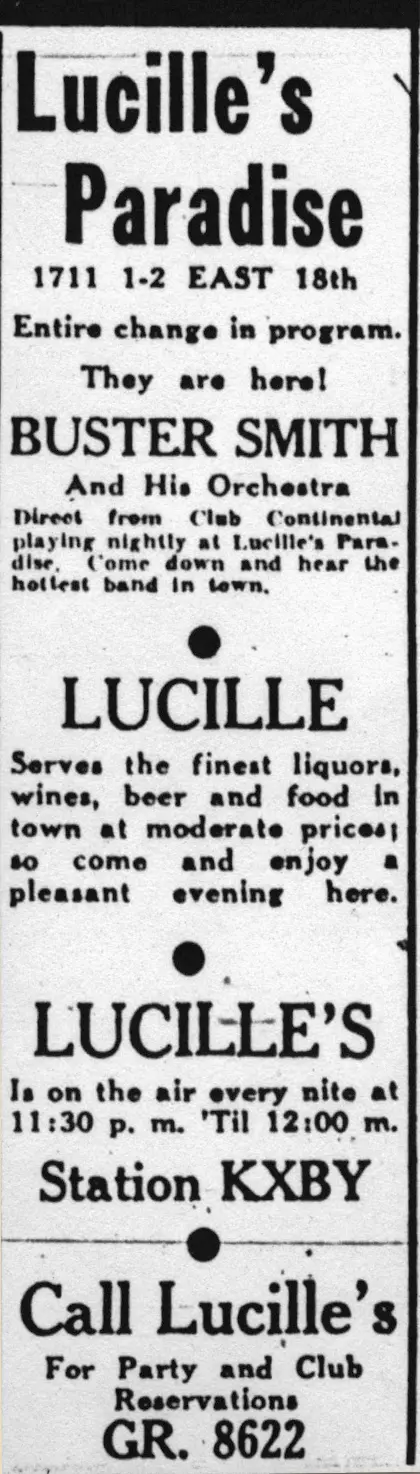

Once back in Kansas City, Charlie became an in-demand soloist. In March 1938, Charlie joined alto saxophonist Buster Smith's band at Lucille's Paradise, a popular nightspot in the heart of 18th and Vine. Smith mentored Charlie onstage, teaching him how play double time and glide in and out of key.

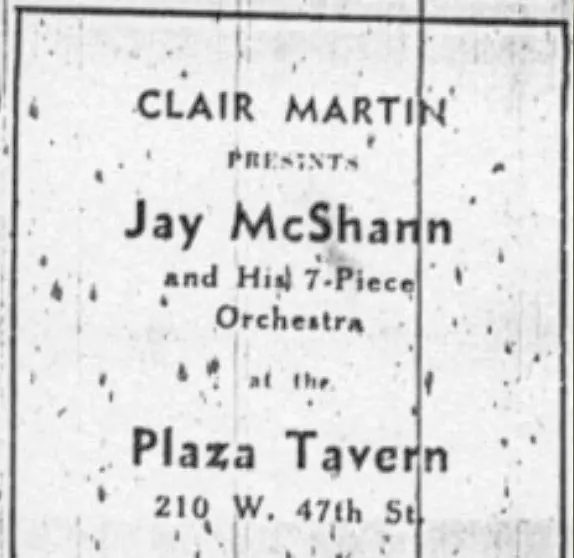

After Smith moved to New York, Charlie joined pianist Jay McShann's band at Martin's on the Country Club Plaza, an upscale shopping district. On the side, he played with drummer Jesse Price's band at the Jelly Joint, a malt shop, frequented by University of Kansas City students.

In November 1938, Charlie switched to the Harlan Leonard Band. Charlie became a star soloist with the Leonard Band, billed as the "Saxophonist Supreme". The no nonsense Leonard soon let the notoriously unreliable Charlie go. Harlan later recalled, "We could never count on him showing up." Feeling dejected and not getting along with Rebecca, Charlie hopped a freight train for New York, hoping to reunite with his musical father Buster Smith.

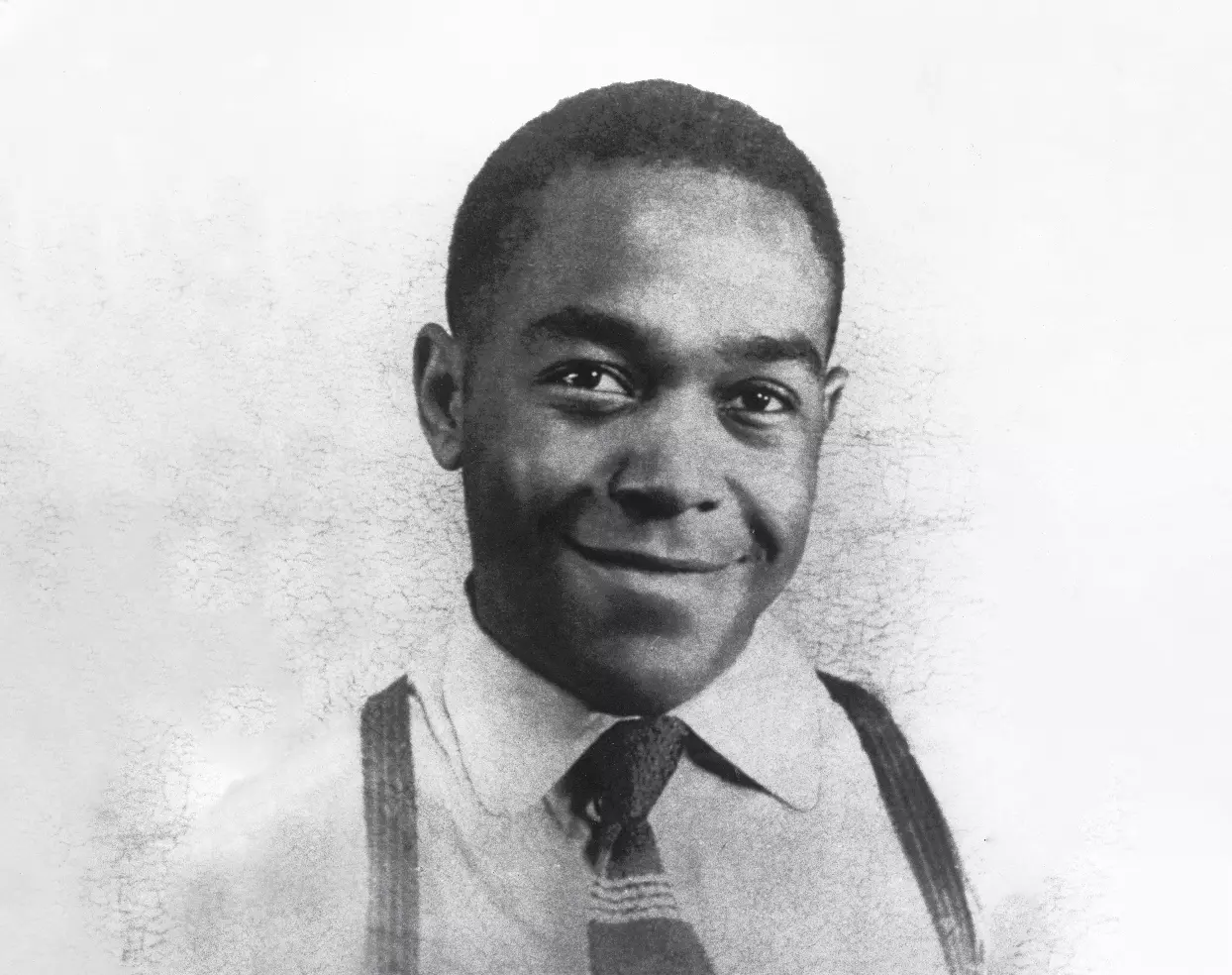

Charlie as a young man

Charlie Parker's portrait in the Lincoln High School yearbook. Courtesy Frank DriggsLucille's Paradise

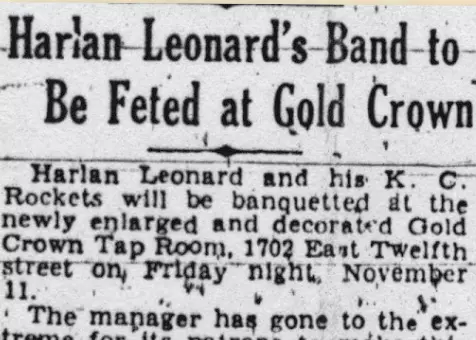

Courtesy Kansas City Call 2/18/38Gold Crown Tap Room Ad

Newly rennovated venue advertises for Harlan Leonard and his K.C. Rockets. Courtesy Kansas City CallGold Crown Tap Room Ad

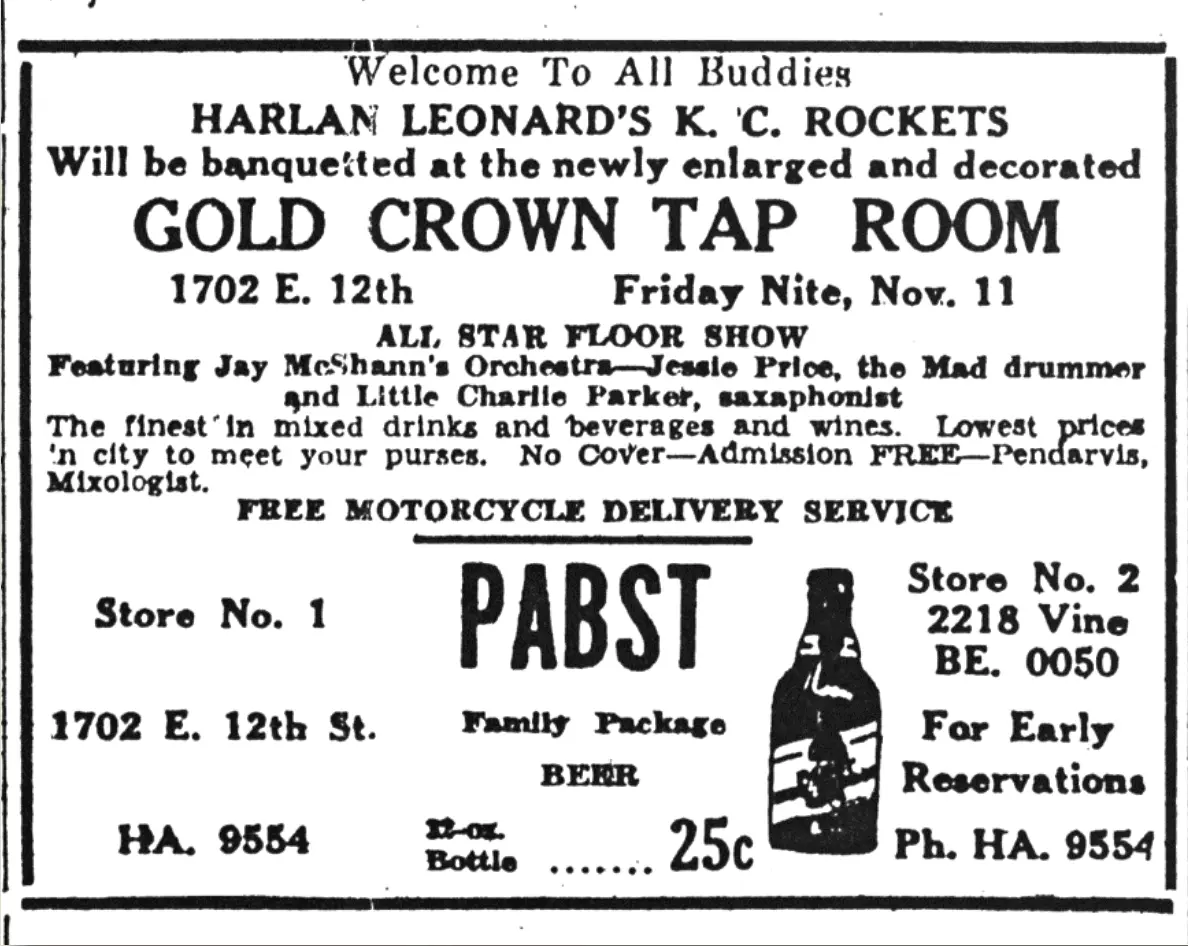

Venue on East 12th Street, Kansas City, MO. promoting the Jay McShann Orchestra with the "Mad Drummer" Jessie Price, and "little" Charlie Parker. Courtesy Kansas City CallYuletide Greetings

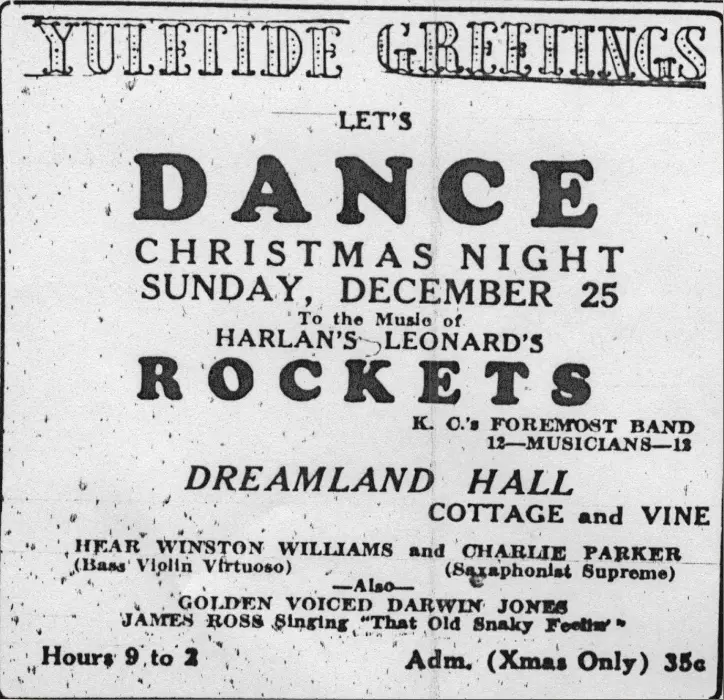

Dreamland Hall at Cottage and Vine Street. Courtesy Kansas City Call 12/23/38On the road with Jay McShann's Orchestra

Charlie Parker is seated fourth from the left. Courtesy Norman SaksMusser's Ozark Tavern

The car Charlie and his band were traveling in flipped before they could play the grand opening of the new resort Three miles south of Eldon, Missouri. Courtesy H. Dwight WeaverClair Martin Presents

Newspaper advertisment for upcoming shows at the Plaza Tavern and the Brookside Tavern. Courtesy Kansas City Journal, 11/4/38McShann and Lee Click

Article on McShann's band attracting attention at the Plaza Tavern and the Brookside Tavern. Courtesy the Kansas City Journal, 11/19/38

Yardbird Takes Wing

A few months after Charlie arrived in New York, he received news from Addie that his father had died. Charlie returned to Kansas City to be with Addie, who warmly welcomed him back home. Charlie freelanced around Kansas City before joining Lawrence Keyes' Deans of Swing. On Easter Sunday 1940, the Deans of Swing battled the Jay McShann Band at the Roseland Ballroom, located at 15th and Troost. After the show, Charlie joined the McShann Band.

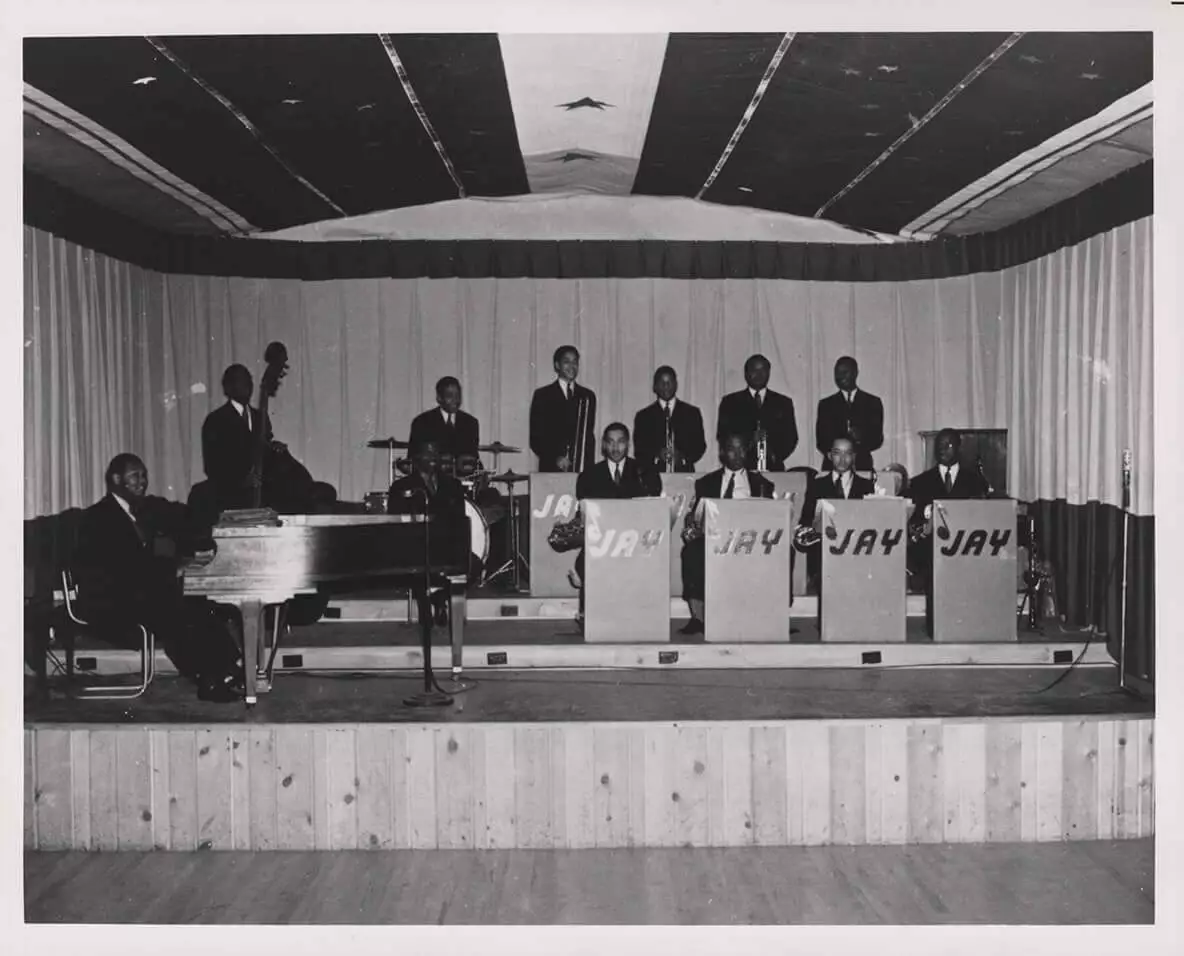

The McShann Band played extended engagements at the Pla-Mor Ballroom, Century Room, Fairyland Park and Tootie's Mayfair. Charlie's reliability and leadership pleasantly surprised McShann. Charlie led the saxophone section and helped Jay develop a book of new arrangements for the band.

The band traveled widely across the Mid-West. Charlie received his nickname during a trip with the band to Lincoln, Nebraska. On the way to Lincoln, the car Charlie was riding in ran over a chicken. Charlie insisted that the driver back up so he could retrieve the "yardbird."

Back at the boarding house, Charlie begged the woman who ran the house to cook the bird. Band members, amused by Charlie's enthusiasm for chicken, began referring to him as "Yardbird."

During a 1940 Thanksgiving weekend engagement at the Trocadero Club in Wichita, Kansas, Fred Higginson a young jazz fan who worked at radio KFBI, recorded the band to instantaneous cut discs during two late night sessions. Charlie's solo flights on "Body and Soul" and "Moten's Swing" highlight his advanced techniques and ideas. It the tune Body and Soul, Charlie runs in and out of key. Triplets in the second eight-bar section and triplet flourishes at the end of the bridge distinguish his solo on "Moten's Swing". These recordings first captured Charlie's emerging genius.

Dizzy, Bird, and Billy Eckstine

Courtesy Frank DriggsBird with McShann in Wichita, KS.

Publicity photo of the Jay McShann Band. Jay McShann Collection, LaBudde Special Collections, UMKCBird taking a solo with the Earl Hines Band.

Courtesy Norman Saks

Hootie Blues

To give band members a feel for the upcoming session, Jay had John Tumino, the band's manager, record the band using a home record-cutting lathe, which recorded to 10" lacquer discs. The February 6, 1941, session produced two sides: "Margie" and "I'm Getting Sentimental Over You." Charlie's lyrical thirty-two bar solo and four bar codetta on "I'm Getting Sentimental Over You" reveals his formidable technique and maturity as a soloist.

On April 30, 1941, the band recorded for Decca in Dallas, Texas. The president of Decca, Jack Kapp's brother Dave supervised the session. The band recorded six songs: "Swingmatism," "Hootie Blues," "Dexter Blues," "Vine Street Boogie," "Confessin' the Blues" and "Hold ‘Em Hootie." Co-written by Jay and Charlie, Hootie Blues featured Charlie's first solo on a commercial release. After the session, Kapp rushed "Confessin' the Blues" and "Hootie Blues" into production.

The release of "Confessin' the Blues" backed by "Hootie Blues" caught Jay by surprise. "We went out on the road for a couple of months," Jay remembered. "We came into Tulsa, Oklahoma and ran into a guy who told us he just heard our record at Jenkins. We didn't know the records had been released." The song "Confessin' the Blues" became one of Decca's biggest hits. Musicians who flipped the disc over and listened to "Hootie Blues" were astounded by Charlie's inventive twelve 12-bar solo.

As "Confessin' the Blues" took the nation by storm, the McShann band stayed in Kansas City for a summer engagement at Fairyland Park. By the fall, "Confessin' the Blues" had sold over 100,000 copies, giving the band the lift it needed to rise nationally.

The Jay McShann Band enters the spotlight

Publicity photo of the Jay McShann Band. Charlie is pictured behind Jay McShann at the piano. Dave E. Dexter, Jr. Collection, LaBudde Special Collections, UMKC"Margie" record

John Tumino Collection, Marr Sound Archives, UMKC"Sentimental Over You" record

John Tumino Collection, Marr Sound Archives, UMKCDizzy, Bird, and Billy Eckstine

Courtesy Frank Driggs

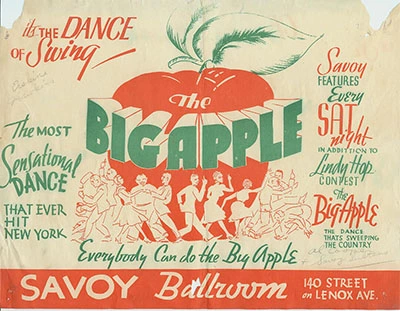

Swinging at the Savoy

On February 13, 1942, the band opened at the Savoy Ballroom on a double bill with the popular Lucky Millinder Band. The Savoy, known as the Home of Happy Feet, was Harlem's leading ballroom. The McShann band arrived road weary and late for their debut in New York. Nevertheless, that evening the McShann band bested the Millinder band in a bare-knuckle battle of the bands. Gene Ramey recalled, "From the time we hit that first note until the time we got off the bandstand, we didn't let up. We heated it so hot for Lucky Millinder that during his set he got up on top of the piano and directed his band from there. Then he jumped off and almost broke his leg."

The McShann band signed with the Moe Gale Agency, one of the nation's top booking agencies. In between tours of the South, the band played at the Savoy. Broadcasts from the Savoy over the NBC Blue radio network introduced Charlie to listeners across the country. Dazzled by Charlie's solos, musicians crowded the bandstand. Dizzy Gillespie frequently sat in with the band at the Savoy.

Charlie and Gillespie became fast friends and musical rivals. After hours, they jammed with other young modernists at Minton's Playhouse, a popular bar and restaurant. Minton's back room served as a laboratory for the development of bebop. Charlie and Gillespie joined Thelonious Monk, Charlie Christian, Kenny Clarke and other young progressive musicians who were experimenting with new harmonic expressions and phrasing that led to the development of this new movement in jazz. Charlie and Dizzy soon emerged as leaders, becoming the first to bring bebop to a broader audience.

Bird and Chet Baker

Courtesy Norman SaksMonk and others outside Minton's Playhouse

Manhattan, New York City. William P. Gottlieb Collection, Library of CongressJay McShann Band at The Savoy

James F. Condell Collection, LaBudde Special Collections, UMKCSavoy Ballroom

Souvenirs of The Savoy. Courtesy Norman Saks

Big Band Bop

The band toured widely, navigating wartime restrictions on gasoline, rubber and other material deemed essential to the war effort. While on the road, Charlie and Dizzy challenged each other on and off the bandstand. After hours, they hunkered down in hotel rooms, woodshedding and refining their new musical ideas. They came together in what Dizzy later described as "one heartbeat."

Traveling across the south, the band encountered racial prejudice at every turn. Band members were glad to return to New York. When Hine announced another tour of the south, Eckstine, Charlie, Dizzy and other band members quit the band. They went their separate ways, but soon reunited in a big band led by Eckstine.

In the summer of 1944, Eckstine formed the first big bebop band. He brought Dizzy aboard as music director and recruited Charlie to lead the saxophone section. Dizzy created arrangements of his compositions, giving the band a distinctive modern style. "Our breathing and phrasing were different from all the other bands and naturally we sounded different," Dizzy related. "There was no band that sounded like Billy Eckstine's. Our attack was strong, and we were playing bebop, the modern style. No other band like this one existed in the world."

The Eckstine Band was short-lived. Unable to tour widely because of wartime restrictions on gas and rubber, Eckstine's big band gradually fell apart. In September 1944, Charlie left the band and joined saxophonist Ben Webster's band at the Onyx Club on 52nd Street. Shortly after, Dizzy left the band and formed a small combo with Charlie. Together they sparked a bebop revolution.

Jazz Festival International Poster

Courtesy Norman SaksSnapshot of Billy Eckstine at the Apollo

Buck Clayton Collection, LaBudde Special Collections, UMKCCaricature illustration for Earl Hines

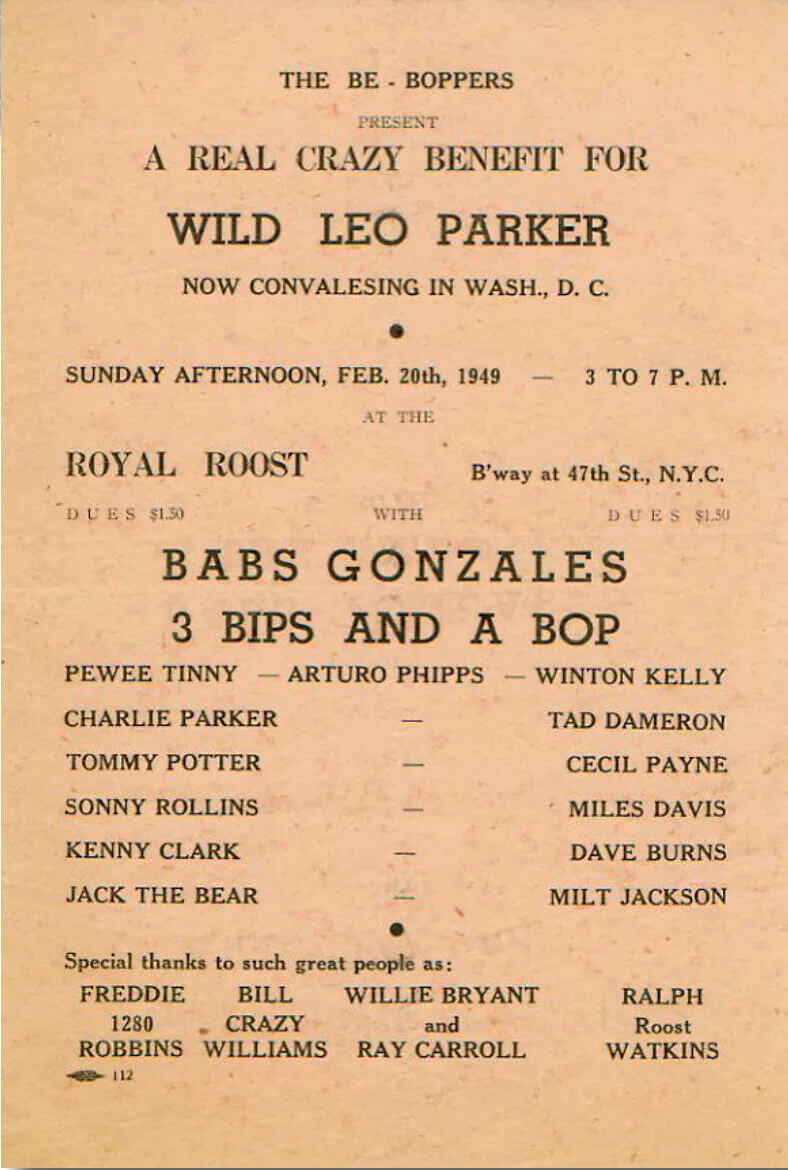

Dave Dexter Jr. Collection, LaBudde Special Collections, UMKCBenefit poster

Courtesy Norman SaksAutographed publicity photo of Charlie Parker

Courtesy Norman Saks

52nd Street

The quintet featuring Max Roach on drums, Curly Russell bass and Bud Powell piano, defined and set the standard for the still-emerging bebop style. Charlie led the way. Dizzy recalled "Before I met Charlie Parker my style had already developed, but he was a great influence on my whole musical life. The same thing goes for him too because there was never anybody who played any closer than we did... Sometimes I couldn't tell whether I was playing or not because the notes were so close together....The enunciation of the notes, I think, belonged to Charlie Parker because the way he'd get from one note to another....Charlie Parker definitely set the standard for phrasing our music, the enunciation of notes."

In July 1945, the quintet closed at the Three Deuces. Dizzy and Charlie temporarily parted ways. Dizzy assembled a big band and Charlie formed a small combo, becoming the leader of his own group for the first time. The next month, the Charlie Parker Quintet opened at the Three Deuces to rave reviews. Metronome columnist, Leonard Feather proclaimed, "Parker is the most phenomenal and frantic alto man ever."

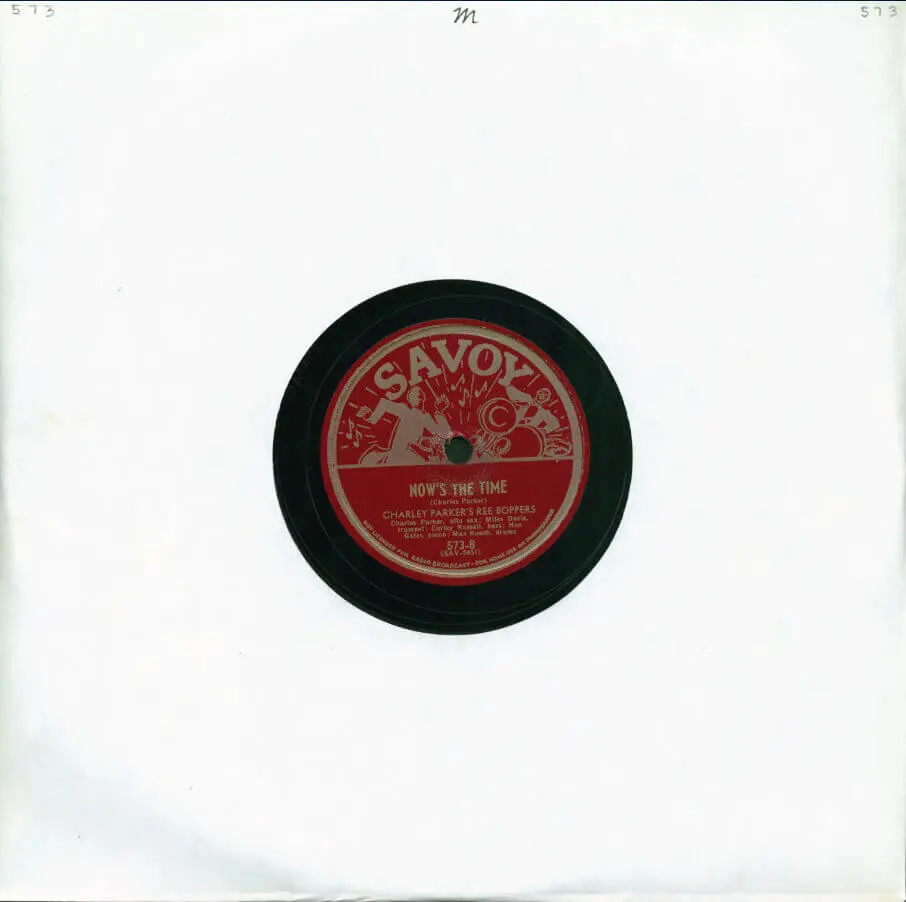

Charlie's critical acclaim led to his first recording session as a leader. In November 1945, Charlie recorded six sides in a hastily arranged session for the Savoy Label. Now's the Time featuring Miles Davis on trumpet and Dizzy Gillespie on piano highlights Charlie's Kansas City roots and deep feeling for the blues. Having opened on 52nd Street and recorded with his own group, Charlie had truly arrived in New York.

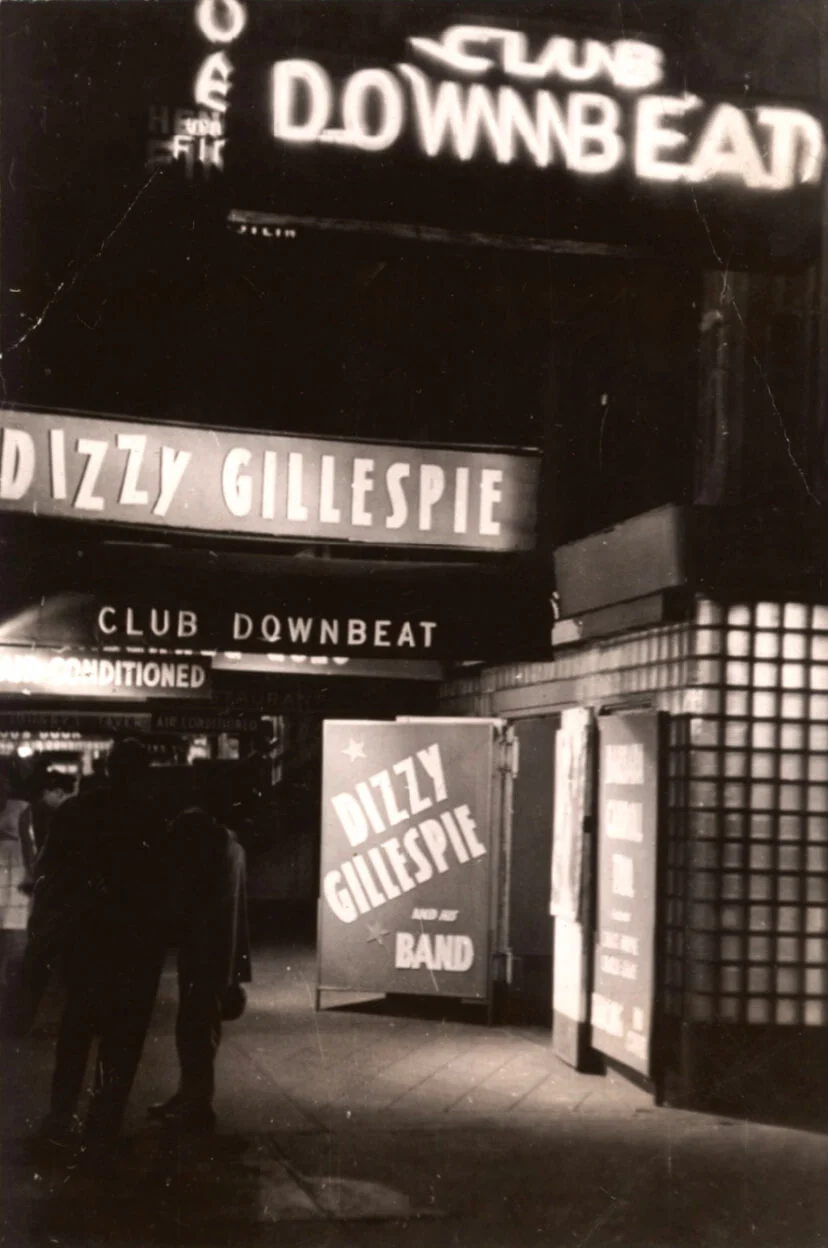

Exterior of Club Downbeat

Buck Clayton Collection, LaBudde Special Collections, UMKCRecord for "Now's the Time"

Marr Sound Archives, UMKCNight time on Swing Street

William P. Gottlieb Collection, Library of Congress

Relaxin' at Camarillo

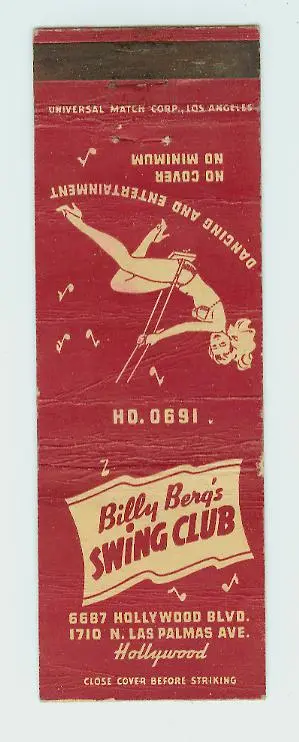

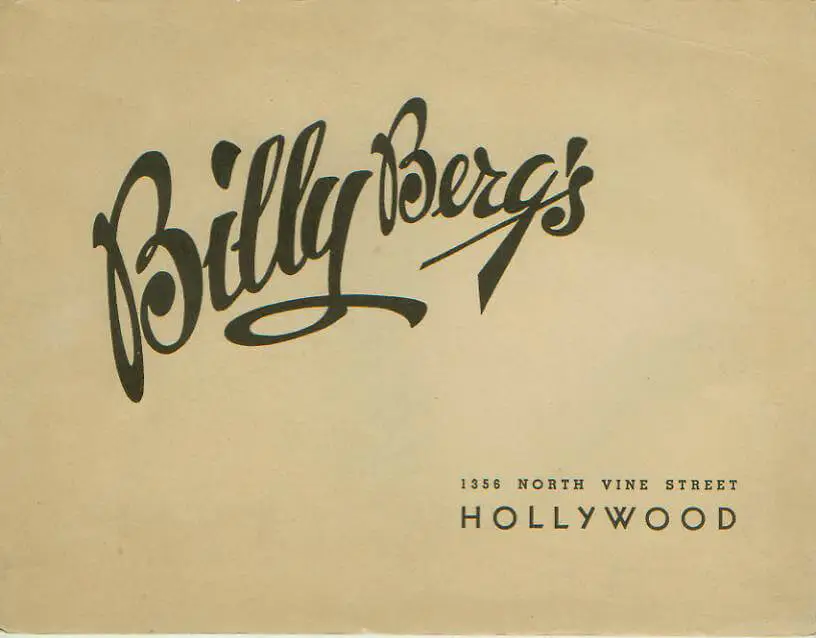

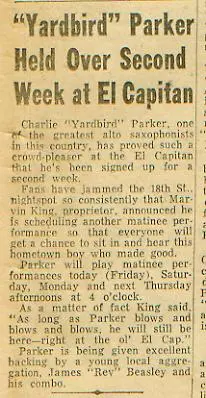

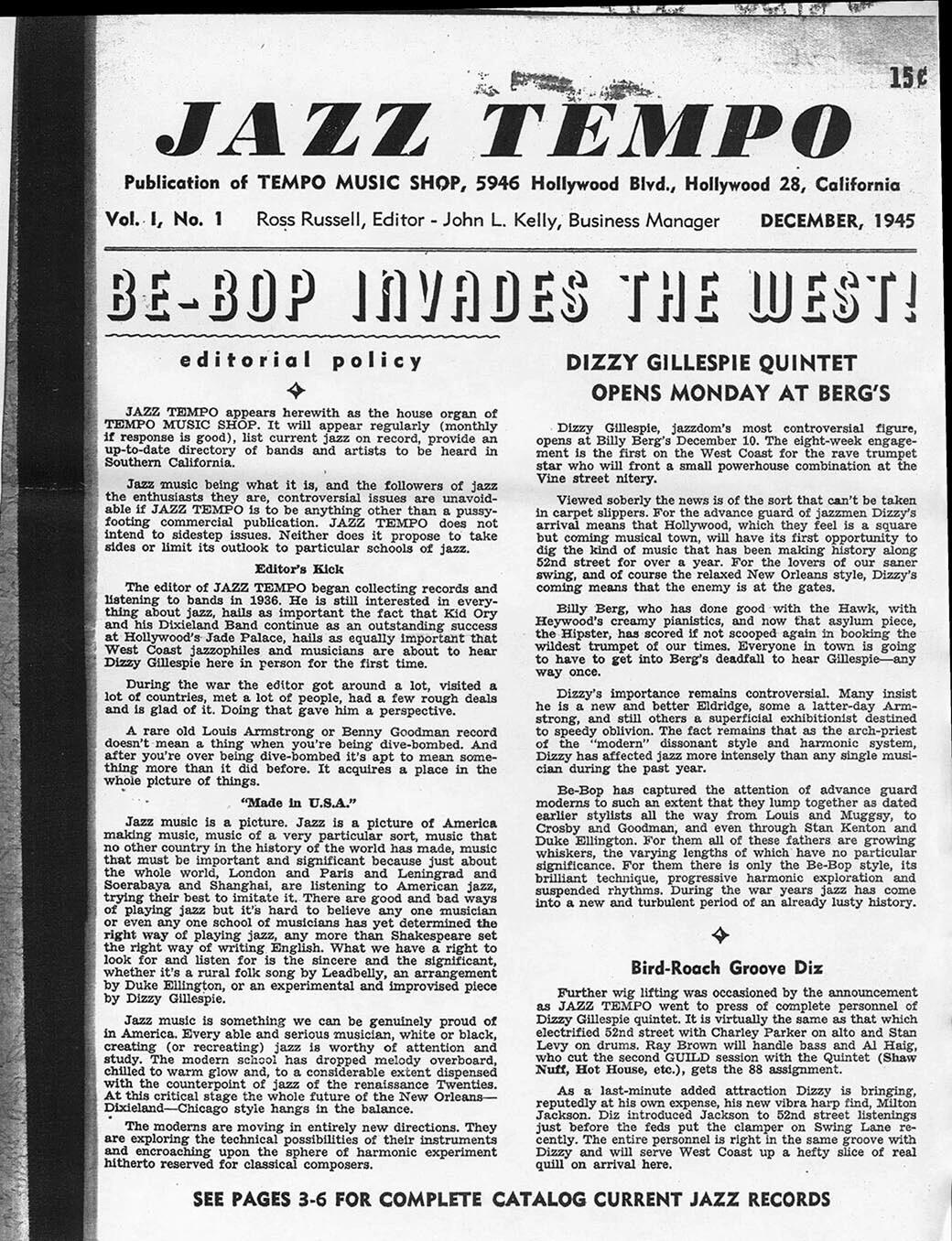

Los Angeles jazz fans were not ready for the new music. Crowds of hipsters and musicians flocked to the club for the first week to check out the new music. Attendance during the second week slumped. Dizzy recalled, "We hit some grooves on the bandstand at Billy Berg's....but the audience wasn't too hip. They didn't know what we were playing, and in some ways, they were more dumb-founded than the people down South. Just dumb-founded."

When the quintet closed out at Billy Berg's in February, Dizzy generously bought band members tickets to New York. Charlie cashed out his ticket and stayed in Los Angeles. He found work with trumpeter Howard McGhee's band at the Streets of Paris, Finale Club, and the Hi-De-Ho Club. Charlie encouraged and inspired young players at after-hours jam sessions.

Charlie struggled with alcoholism and drug addiction. He developed a taste for heroin while recuperating from his car wreck in the Ozarks. When heroin became scarce in Los Angeles, Charlie began drinking heavily. His health declined rapidly, manifested by mental disorientation and sudden jerky movements of his limbs.

During a recording session for Ross Russell's Dial Label, Charlie suffered a mental breakdown that landed him in Camarillo State Mental Hospital, located 45 miles north of Los Angeles. Charlie settled into the routine, tending to a lettuce patch and playing in the band on Saturday nights. After six months of therapy, the staff at Camarillo discharged Charlie to the custody of Ross Russell.

Russell, eager to launch his fledgling Dial Record label, ushered Charlie into the studio. Charlie and the band cut four sides including a 12-bar blues Russell dubbed Relaxing at Camrillo. Once released, " "Relaxin' at Camrillo" won Charlie his first international acclaim—the prestigious Grand Prix du Disque award in France.

Matchbook from Billy Berg's

Courtesy Norman SaksRecord for "Relaxing at Camarillo"

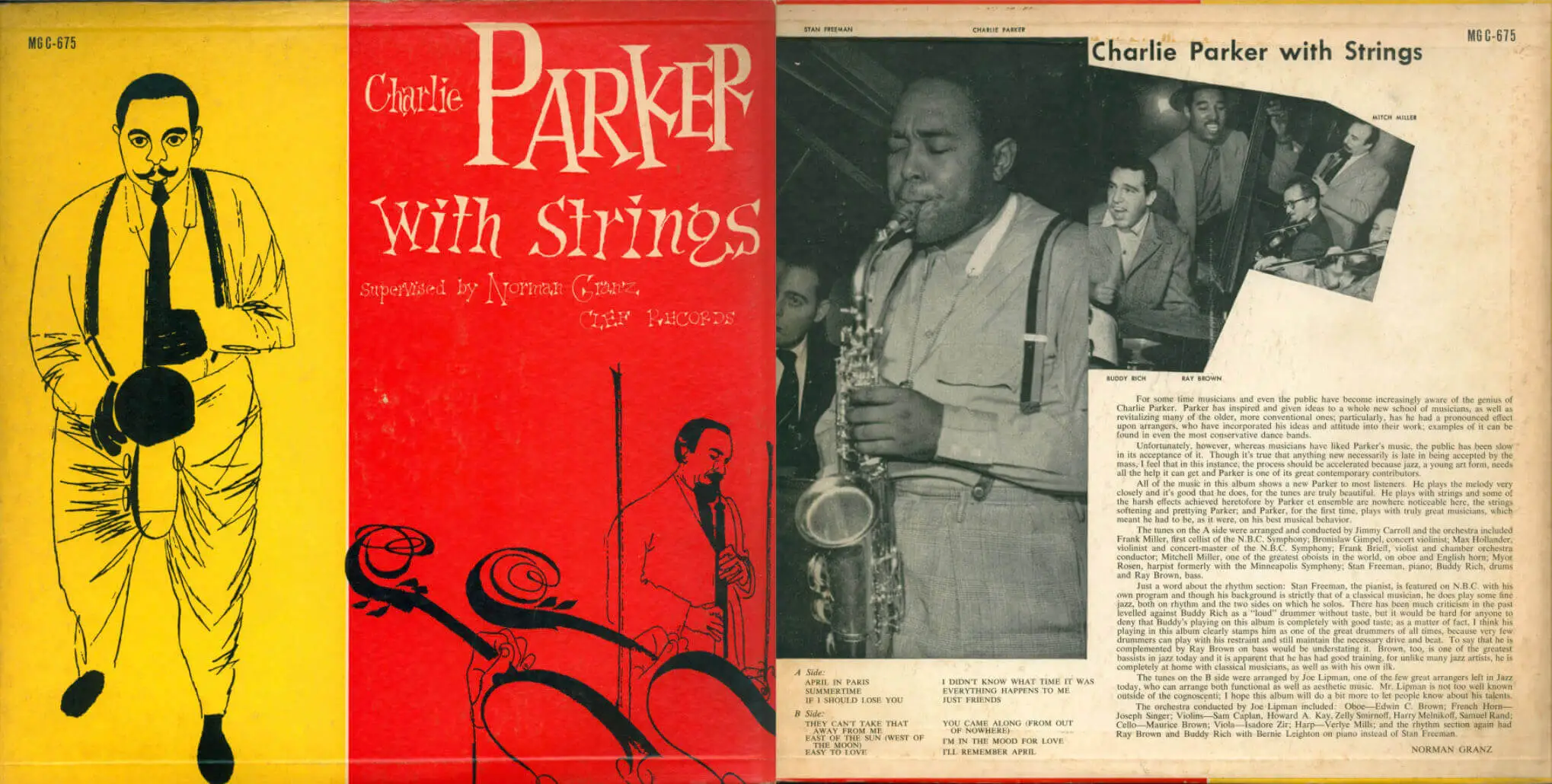

Marr Sound Archives, UMKC"Charlie Parker with Strings" album art

Marr Sound Archives, UMKCPromotional ephemera from Billy Berg's

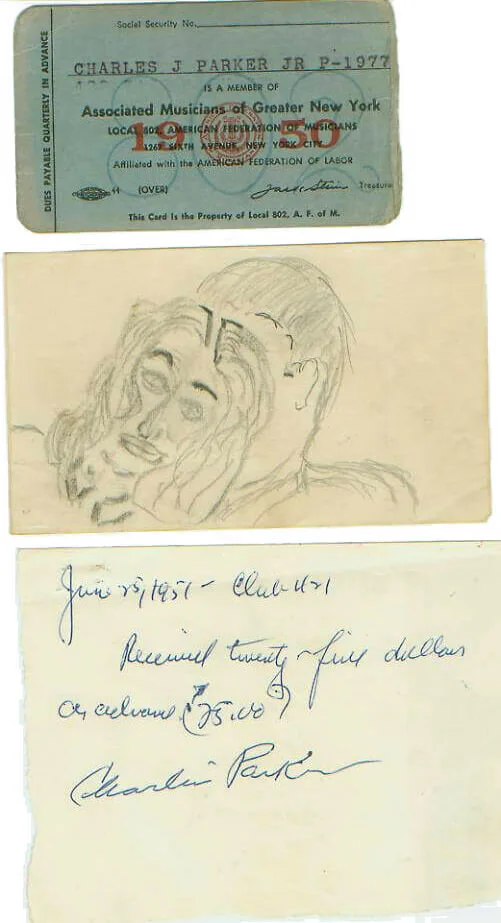

Courtesy Norman SaksNotes written by Charlie Parker

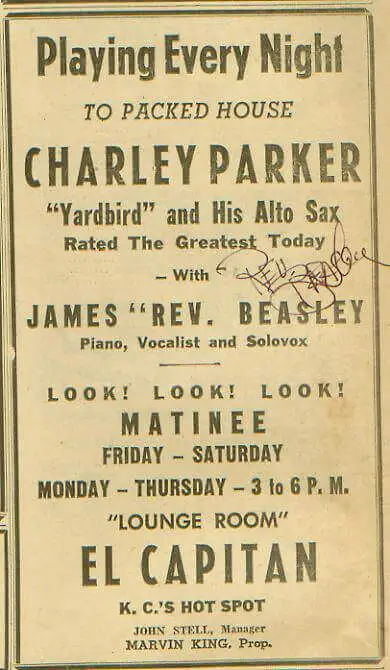

Courtesy Norman SaksKansas City Call Newspaper Ad, July 25, 1952

Courtesy Norman SaksKansas City Call Article, July 25, 1952

Courtesy Norman SaksPhotocopy of Jazz Tempo Magazine article publicizing Parker and Gillespie's showcase at Berg's

Courtesy Norman SaksAshtray from Billy Berg's

Courtesy Norman SaksBird with King Horn Magazine Ad

Courtesy Chuck Haddix

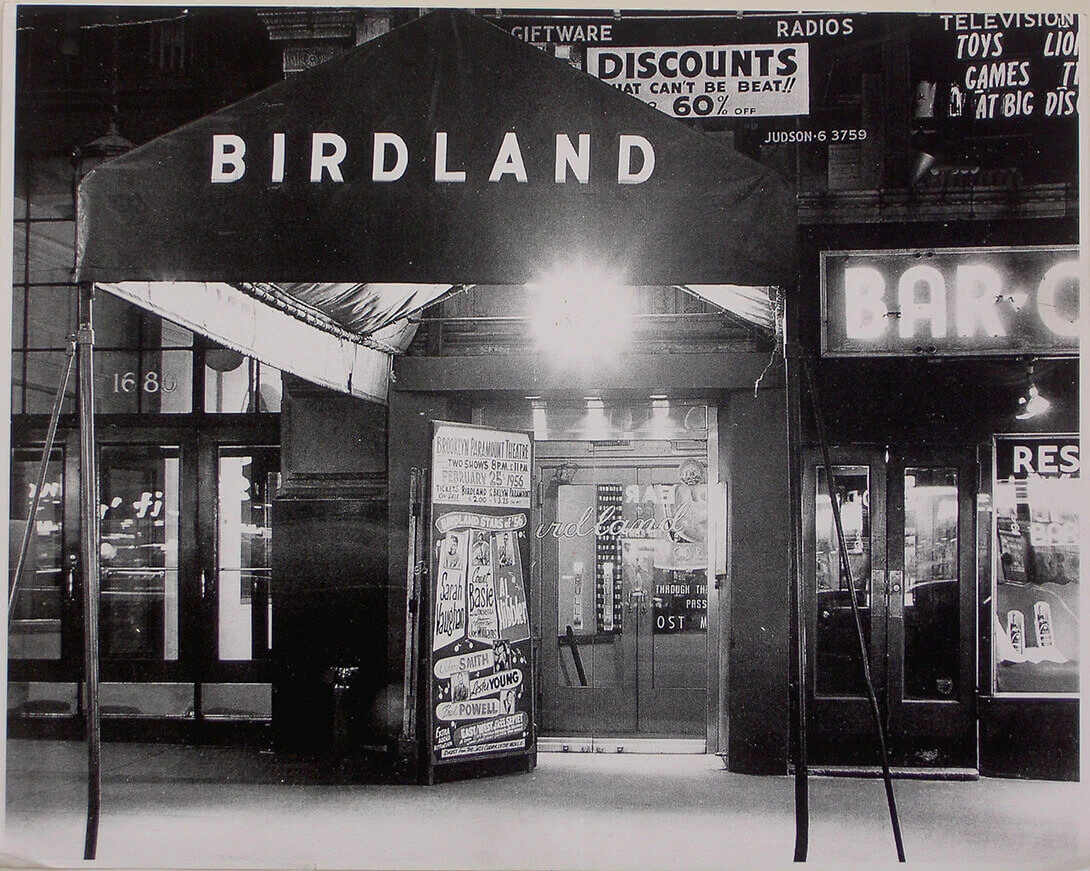

Birdland

In between playing club dates on 52nd Street, Charlie toured nationally with his own quintet and as a star soloist with Norman Granz's Jazz at the Philharmonic, a traveling concert featuring top jazz stars. Since Jazz at the Philharmonic's inception in Los Angeles, the concert series had grown from a free-wheeling jam session into an institution, playing stately halls and auditoriums giving jazz the same dignity afforded to classical music. Granz paid musicians well and insisted they be respected as artists and individuals regardless of the color of their skin.

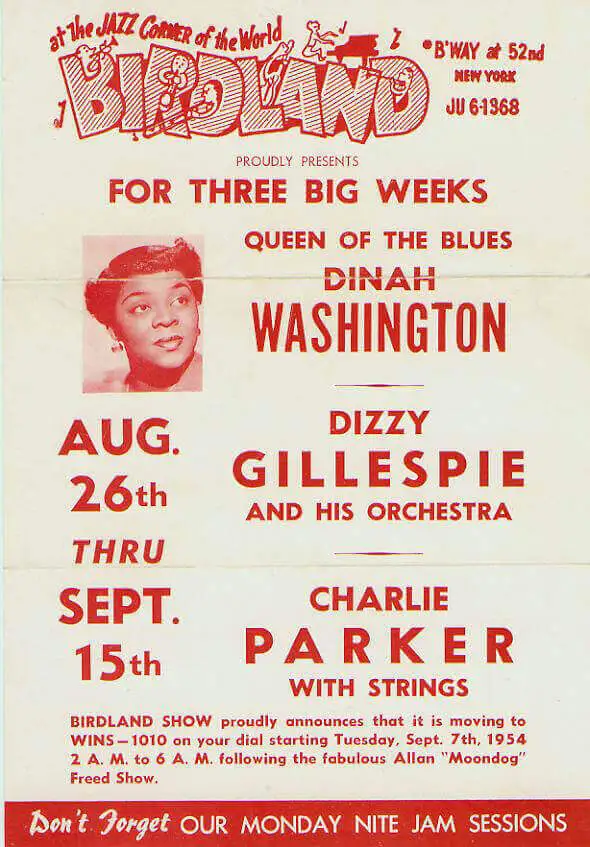

Charlie's relationship with Norman Granz paid off handsomely for both men. In November 1949, Granz recorded Charlie with a string section. Charlie, who loved classical music, excitedly embraced the project feeling that recording with strings legitimized his music. Sticking closely to the 32-bar popular music form, Charlie recorded six of his favorite standards accompanied by a chamber ensemble and a jazz rhythm section. With the exception of his solo on "Just Friends", Charlie ironically played the melody straight instead of improvising on the changes.

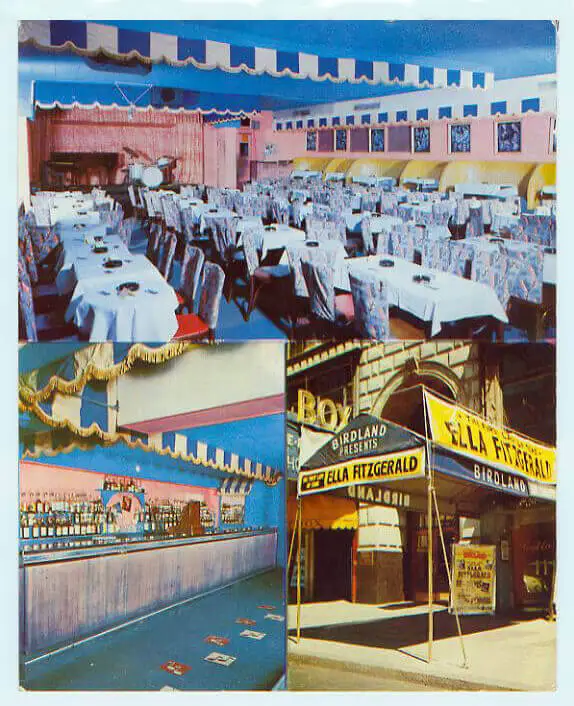

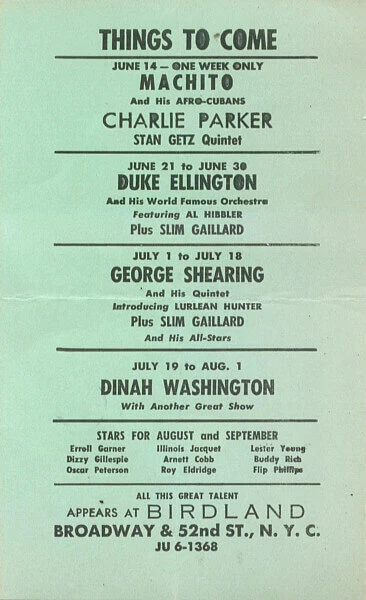

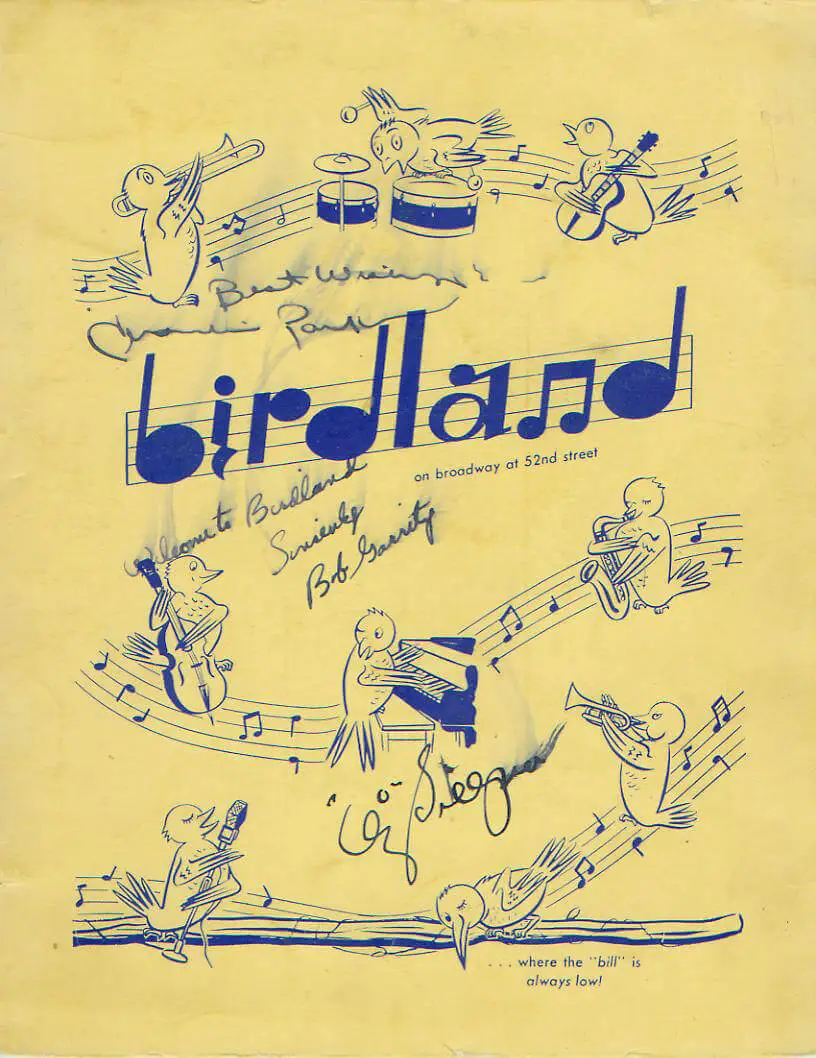

Birdland postcard

Courtesy Norman SaksPerformance poster for a show at Birdland

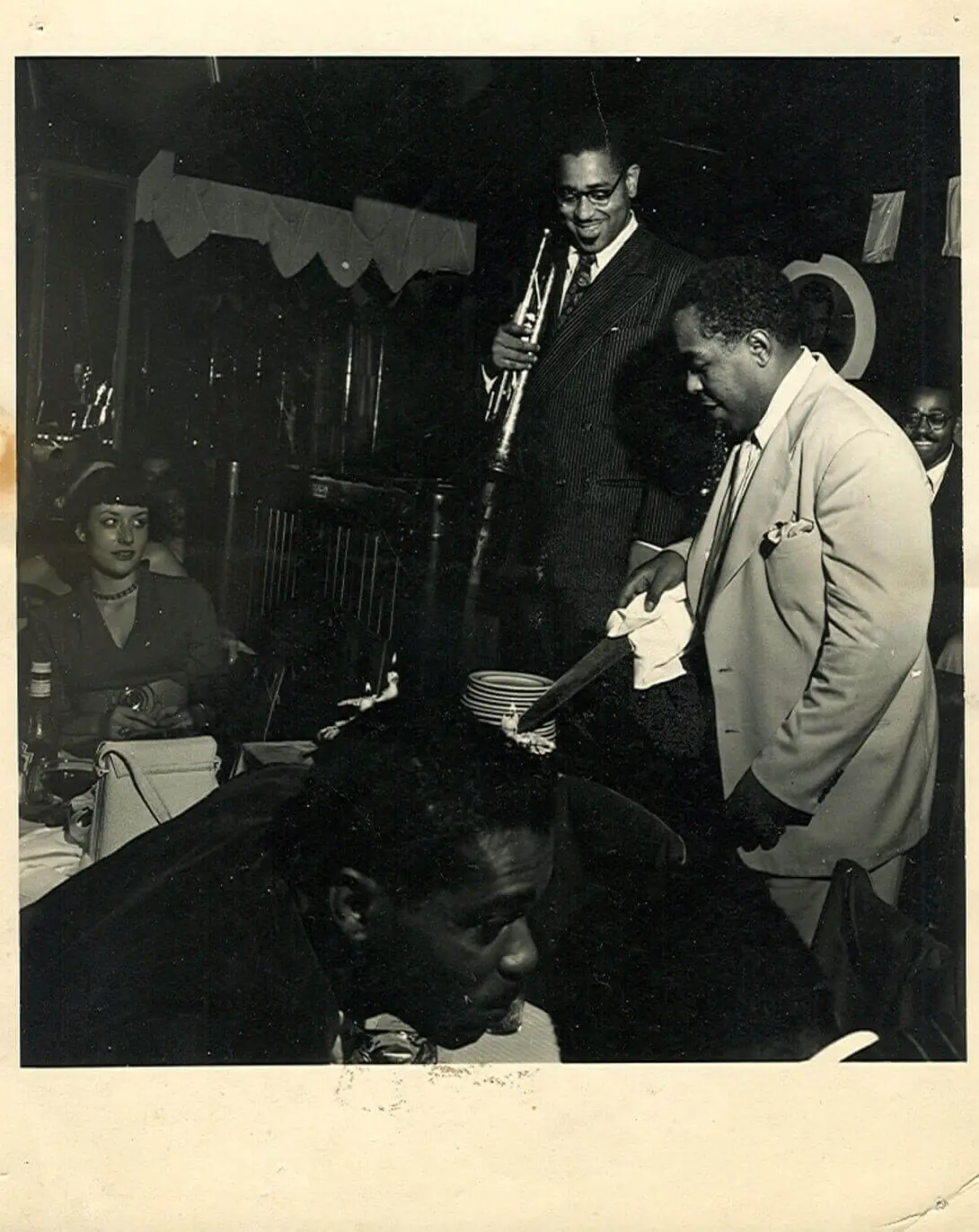

Courtesy Norman SaksBird cuts a cake while Dizzy watches from the stage

Courtesy Norman SaksDizzy performs with the band as Bird watches from the crowd

Courtesy Norman SaksBirdland flier for upcoming performances

Courtesy Norman SaksMenu from Birdland

Courtesy Norman SaksParker performs with a string section

Courtesy Norman Saks

Parker's Mood

Charlie's reaction to Pleasure's version of Parker's Mood led to speculation among jazz fans and friends that he was unappreciated in Kansas City and did not want to be buried in his hometown. Nothing could be further from the truth. After leaving Kansas City, Charlie often returned home to be with Addie, play gigs and spend time with friends in the 18th and Vine area, where he was revered. A close childhood friend Jeremiah Cameron recalled, "The last time I saw Parker as he was coming from his mother's house on 15th and Olive, a year before his death. If he hated Kansas City, it was not reflected in his friendship with me."

The year 1951 began with great promise for Charlie—professionally and personally. His career flourishing, Charlie had just started a family with Chan Richardson, the love of his life. Over the next four years, Charlie's struggles with addiction, alcoholism, and mental health unraveled his life and career. Cut loose from his stable domestic anchor, Charlie drifted off into the New York nightlife, drinking excessively and sleeping wherever he could.

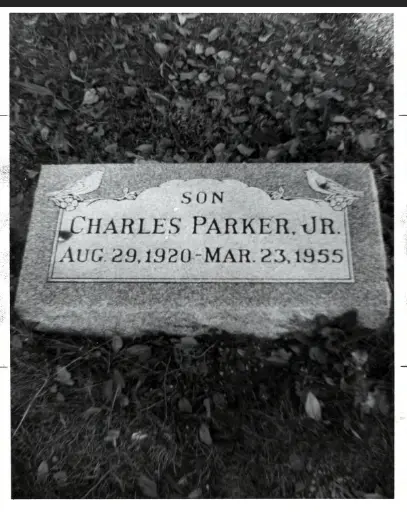

On March 12, 1955, Charlie died in the suite of the Baroness Pannonica de Koenigswarter in the Hotel Stanhope located on 5th Avenue across the street from the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Chan wanted to bury Charlie in upstate New York next to their daughter Pree, but Charlie's third wife Doris and Addie intervened and brought Charlie's body back to Kansas City. A simple granite headstone adorned by two small birds marked Charlie's grave in Lincoln Cemetery. Unfortunately, the stone bore an incorrect date of death as March 23.

Back in New York, a more fitting epitaph scrawled in crayon and chalk on fences, sidewalks and buildings appeared across Greenwich Village. Led by poet Ted Joans, the hipsters, writers and poets who followed Charlie in life immortalized him in death with the bold declaration—BIRD LIVES.